July 23, 2024

Director's note: Fidelio

Fidelio has consistently served as a symbol of hope for generations of people afflicted by oppression: a revival in 1814 served as a protest against Napoleon's autocratic tyranny; an Arturo Toscanini led performance in 1937, as well as a Bruno Walter conducted Metropolitan Opera performance in 1941, affirmed the dignity of humanity and the countless victims escaping Europe's Nazi terror; performances of Fidelio in 1954 following the death of Stalin became a statement of outrage for those who were unjustly condemned to the regime's prisons. Each performance reaffirmed and celebrated the power of humanity to defeat tyranny and overcome oppression. The questions we now ask ourselves are: Who is afflicted by oppression globally? What does shining a light on injustice look like? How is true freedom achieved?

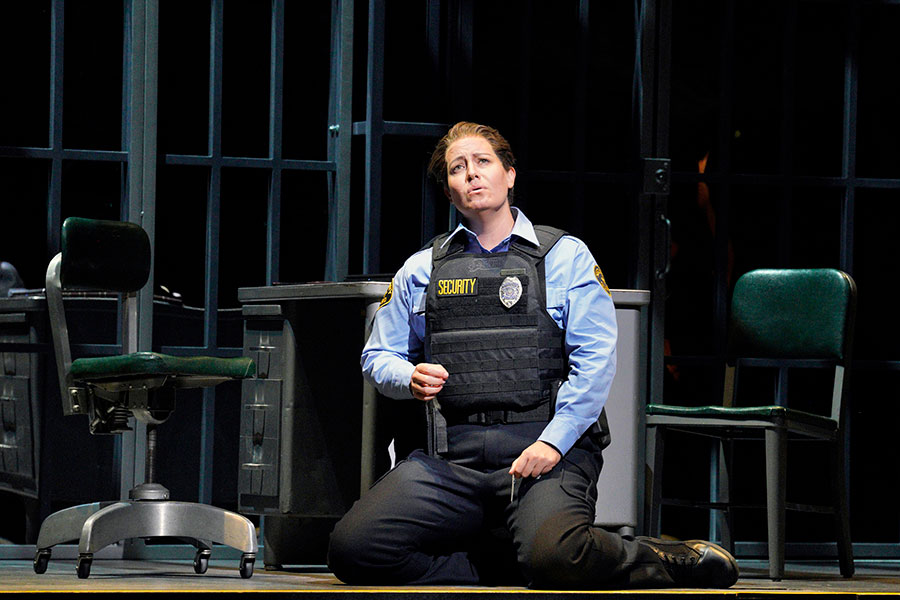

Beethoven's only opera is demanding, revolutionary, and shockingly relevant. It is a story of hope, self-sacrifice, love, and liberation. At the heart of Fidelio is the heroism of a woman, Leonore, a vision for the modern age, whose personal sacrifice to free her husband from wrongful incarceration results in the liberation of all those imprisoned in a state facility. Far from the customary roles for women in opera, Leonore's courage and bravery are empowering. Driven by a noble and just cause, as well as immense love for her husband, Leonore fights from within the "system" and thus becomes a medium for the liberating light that frees all those who suffer in darkness. Her heroic exposure of injustice reminds us that we, too, have the power to be agents of change. Each person deserves the opportunity for their voice to be heard, and each small action carries the potential to create immense ripples in the wave of revolutionary freedom.

Soprano Elza van den Heever as Leonore/Fidelio.

The frame that holds Leonore's journey is that of a prison, and the narrative sharply spotlights the many perspectives and tiers of power embedded within such a facility. On one end of the spectrum are workers in the facility, where those controlling and propping up the "system" are disconnected from the oppression they are upholding. On the other end are those completely without power: the prisoners, and, at the very bottom, Florestan, Leonore's husband, who is silenced for speaking truth to power. In order to navigate such a divide, Leonore must transform herself into Fidelio to keep from being othered or outed in her pursuit to find and free her husband.

Beethoven's intention to choose such a location and story perfectly reflects his revolutionary and humanistic leanings. Living during the Enlightenment era, he was impacted by Europe's renewed optimism that democratic progress would consolidate egalitarian ideals, ideals proclaiming that people deserve equal rights and opportunities. Enlightenment ethos elevated principles of freedom and civility, with the hope of creating a utopia that would decrease the disparity between the wealthy and impoverished. These ideals ignited the French Revolution in 1789. However, as in many cycles where power is threatened, they were quickly crushed by the Reign of Terror, as well as the economic and social injustices nurtured by the Industrial Revolution. Emerging from this feverish time in history were many dramas that highlighted patriotic and political themes, such as unjust imprisonment, escape, and heroic rescue. One such drama was Léonore, ou L'Amore conjugal, which became the basis for Fidelio.

Early on it became clear that our production wanted to mirror the dualities inherent in the narrative and music. How could we visually manifest Beethoven's surging expression and juxtaposition of sonorities? How could we create a structure that would depict the facility, the system, and the tiers of people who inhabit it? We were cognizant that the opera's original setting of the late 18th century was close to the time period in which it was written and premiered. It would have felt very contemporary and relevant to those that saw it. Therefore, we set our production in a recent past or near future detention facility, somewhere in the world. This setting allows us to investigate contemporary structures that remove those that are deemed an "other" and a threat and to give voice to those who have been powerless to speak. In doing so, not only do we aim to honor the rich history and spirit of the work but also recognize the countless people who have overcome oppression, fought for liberty, and have been agents of change. Might we all learn from Leonore's journey and celebrate the power of love and collective action.