March 08, 2024

Aida: war, enemy of love

Often viewed as simply a clash between nations, Verdi's great war tragedy derives its power from profoundly personal interactions.

Aida (1871), the last opera of Giuseppe Verdi’s late middle period — with a long gap before his two dazzling final collaborations with Arrigo Boito, Otello (1887) and Falstaff (1893) — is among his most beloved. Its sheer number of performances puts it at or near the very top of all operas, worldwide, despite the special difficulties of staging a work requiring such large human (and sometimes animal!) forces. Aida is universally admired for the daring and passion of its music, and it is loved, too, for its dazzling spectacle. Most of all, however, it draws us through its tragic human drama.

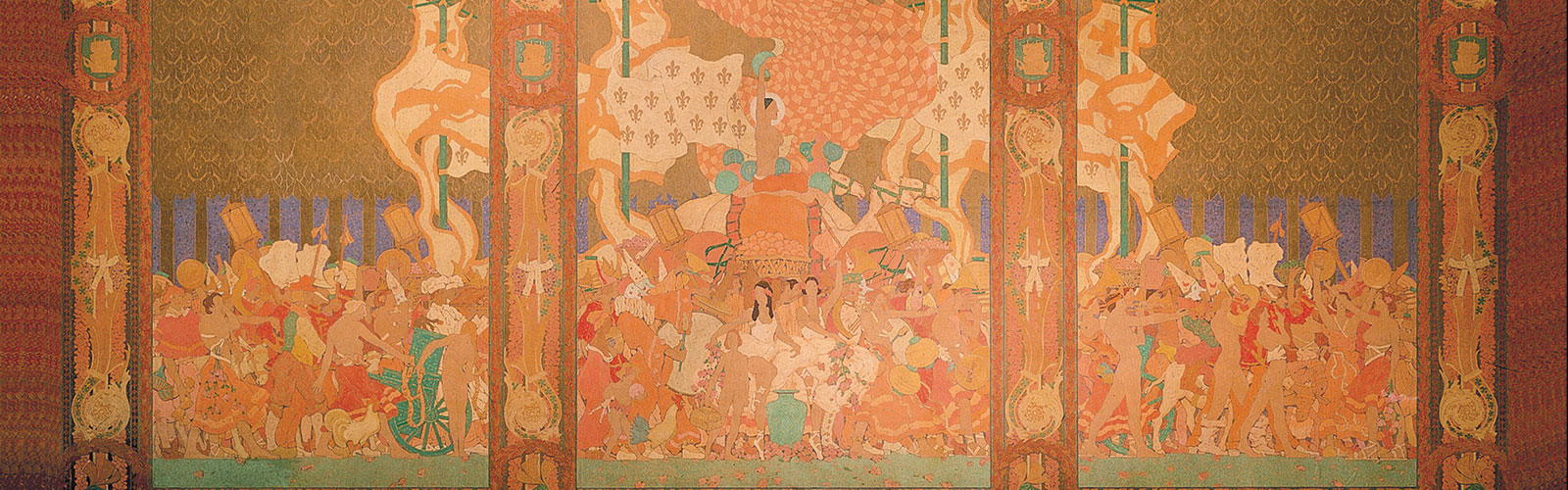

Today we find two common misconceptions about Aida. The first is that it is primarily a pageant, an outward-facing, grand spectacle. True, Verdi loved spectacle, and the opera certainly has some — but spectacle is the least of the work’s achievements. Its famous triumph scene is relatively static and therefore hard to connect to the heart of the drama. At its core, Aida is a very private work. Much of it consists in intimate exchanges among three people, and great portions are soliloquies. Even in the intimate scenes, much is communicated through asides, inner reflections of thought and emotion.

The second misconception is that Aida is a drama of colonial oppression and enslavement, with the Ethiopian Aida standing for the long colonial subjugation of Black Africans. Modern casting often follows this idea, and the opera has given welcome and long overdue opportunities to some great Black singers. Actually, however, as we’ll see, the drama concerns not colonial domination but an ongoing and seemingly endless sequence of retributive wars between two powerful independent kingdoms. War is the culprit, the destroyer of love.

Teatro alla Scala, Milan, Italy, where Aida received its Italian premiere.

War was also the opera's immediate context. No sooner had the Austro-Prussian War ended in 1866 (well for Italy, which achieved unification and nationhood), than it was followed by the Franco-Prussian War, July 1870-January 1871. This war included a siege of Paris, whose destruction Verdi greatly feared, and resulted in the unification of Germany, which filled him with alarm. Moreover, because the Germans took over Alsace and Lorraine, the seeds of future conflict were sown; that war is now seen as a direct precursor of World War I. Let us follow the history of the opera's composition at this ominous time.

In the mid-19th century, Egypt was a relatively autonomous kingdom within the Ottoman Empire, under the governance of a Viceroy, or Khedive, who at this time was Isma'il Pasha. For the opening of the Suez Canal in November 1869, the Khedive, through an emissary, implored Verdi to write something; Verdi declined, and the task was undertaken by Temistocle Solera, an old collaborator of Verdi's and author of the libretti for five early Verdi operas, including Nabucco (1841) (whose plot is remarkably similar to that of Aida, with a similar romantic triangle). He and Verdi were no longer on speaking terms, because Solera had left town with the libretto of Attila (1846) still unfinished. By 1869, Solera had become a minor functionary of the Italian government. The Khedive offered him a post in Egypt, putting him in charge of the Suez ceremonies. (By 1871 he was back in Italy, running an antique shop in Florence.)

By early 1870, Verdi's position had softened, and he let it be known that he might write something for the opening of the Khedival Opera House if a suitable historical plot on an Egyptian theme could be found. Soon thereafter, a scenario for such an opera appeared, and was sent to Verdi by the Khedive through the impresario Camille Du Locle, with whom Verdi often worked. Auguste Mariette, a French Egyptologist residing in Cairo, was apparently the author. Mariette clearly wanted credit for the piece, and authority to addfurther "local color." But he coyly said several different things about its provenance: sometimes that he had created the entire thing, sometimes that he and the Khedive wrote it together, sometimes that "an important person" was the author. When Verdi read the scenario, he liked it very much, but he did not believe that a scholar was the author. It was too dramatically adept, and must be the work of "a very expert hand, one who knows the theater very well." Mary Jane Phillips-Matz, a Verdi biographer, argues that the author was probably Solera, at that time an important person in the Khedival art-world, but unable to work with Verdi under his own name because of their prior rupture.

An 1886 portrait of Giuseppe Verdi by Giovanni Boldini.

Whatever the solution to the enigma, Verdi was excited by the scenario, and began his own study of ancient Egyptian history, reading both Heliodorus of Emesa's novel Aithiopika, the scenario's source, and the Greek historian Herodotus's account of ancient Egypt. He agreed to a contract to deliver the opera for presentation at the end of 1870. At this point, Mariette disappears from the scene. Verdi engaged Antonio Ghislanzoni, a librettist with whom he had recently worked on the revised version of La forza del destino.

Many letters from Verdi to his librettist survive. They show him in charge of every line and phrase, insisting on fidelity to situation and fidelity to character. Again and again, he asks Ghislanzoni to dispense with poetic flourishes in favor of straightforward speech with dramatic meaning; the phrase la parola scenica ("dramatic speech") appears repeatedly. Eventually the work was completed, but war had broken out, and Paris was under siege. The costumes and sets were stuck there, and the premiere had to be postponed. Rigoletto was performed instead on the planned date. After the war ended, Aida was performed to great acclaim on December 24, 1871 — but not with the singers Verdi preferred, so he always counted the Milan premiere of February 8, 1872, at which the title role was played by his favorite soprano, Teresa Stolz, and Amneris was sung by Maria Waldmann, a mezzo whom Verdi much admired, as its real debut.

But what is Aida about? Let's now return to the issue of colonialism. Starting in the 17th century, colonial conquest by the great European powers subdued many parts of Asia, Africa, and the Americas, often for centuries. Sometimes there was a war of subjugation, usually against totally unequal forces. Sometimes, as in North America, the colonizers pretended the land was unsettled, and that they were developing a previously unowned space. Typically the colonized people possessed little or no political voice, even though most of them had been autonomous kingdoms before that. The usual purpose was profit. In many cases, the subjugated people worked the land, extracting produce or minerals that were then sent back to Europe. In other cases, the work was done by slaves imported from elsewhere. Always subjugated, sometimes the people of a colony were literally enslaved as well.

Teresa Stolz, Verdi's preferred soprano, in costume as Aida.

Seen in this framework, Aida would be the story of an enslaved person rounded up and sold as property to the Egyptians — standing, in the story, for a European power. This power has conquered Ethiopia and enslaved its inhabitants, not as prisoners of war, but as possessions.

This reading simply does not fit the libretto we have. First of all, the era is wrong. The libretto is based on the Aethiopika of Heliodorus of Emesa (200-300 CE), set in the Old Kingdom of Egypt, whose usual dates are 2700-2200 BCE — thus predating by some 3,500 years the era of colonial slavery. Nor is ancient Egypt a European power; it is an African kingdom.

This is not decisive, however, since Verdi could have introduced issues belonging to his own time into the remote ancient setting. But in examining the libretto, we are presented not with a great power oppressing a weak subjugated people, but rather with two roughly equal great kingdoms who have been making aggressive and retributive war against one another, back and forth, again and again. In the opera's very first sentence, Ramfis says: "Yes, reports say that the Ethiopians dare to try once again ("ancora"), and to menace the valley of the Nile and Thebes." The invaders are said to have burned crops and laid waste to the fields, and the Egyptians fear death and captivity for their own people. Later Amonasro tells Aida that the Egyptians have done the very same thing: "they have desecrated our houses, our temples, our altars, carried our maidens off in chains, slain mothers, the aged, the young." The only reason the Ethiopians have not done the same this time is that their invasion is not successful.

The motive for these reciprocal wars is primarily, on both sides, vengeance for prior invasions and insults. In the tremendous choral scene that begins with the King's "Su! del Nilo al sacro lido accorrete, Egyzii eroi" ("Up! Run to the sacred banks of the Nile, Egyptian heroes") — far more stirring musically, in my view, than the static triumph scene—we see a people galvanized to retributive violence by the thought of both past and present wrongs to their own country. Even the gods are later described as "avengers" ("vindice") of the wrongs done to Egypt by the enemy. The people are in pain, and their cry is "Guerra! Guerra! Guerra guerra guerra!" ("War!") and death to the foreigner ("e morte allo stranier"). So it goes, on and on. If there is any moral high ground here, it belongs to the somewhat naive Egyptians, who, after their triumph, free all the Ethiopian prisoners, believing Amonasro's lie that their king has been slain. Only Amonasro (known only as Aida's father, not as that same king) is kept behind as a hostage, and, as we shortly see, he is free enough to organize his troops and plan a second campaign.

Nor is there any hint of anything like the slave trade of the 18th and 19th centuries. The enslaved are prisoners of war. Aida must have been captured in a prior invasion, long enough ago that they have forgotten that she is the king's daughter; and the Ethiopian captives would no doubt have been selectively enslaved too, had Radamès's plea for mercy not led to their release. The two nations have a visceral hatred of one another: the Egyptians call the Ethiopians "barbari," and Amonasro calls Egyptians a "hated race ("razza"), deadly to us." So far as we can tell, this hatred is based on past ill treatment, not on physiognomy or color.

The 1955 Lyric premiere of Verdi's Aida.

Retributive and more or less unending war, then, is Verdi's theme, not asymmetrical colonial domination. This war scenario is timeless — great powers have behaved this way for millennia, and they were behaving this way still in Verdi's time, as he saw, and keenly felt. Verdi's letters show deep grief and fear about the 1870 war and the future of Europe.

Within this scenario of perpetual back-and-forth war, two themes are of primary interest to Verdi. First is the pain inflicted on captive people by separation from their own country — a theme dear to Verdi's heart always, as in the famous chorus of the Jews in Nabucco, "Va pensiero" ("Go thoughts"), one of his most memorable creations, and in the similar lament, "Patria oppressa," sung by the Scottish refugees in Macbeth. Here in Aida, however, he gives the longing for a lost fatherland not a choral but a deeply personal form — Aida's hauntingly beautiful aria "O patria mia" (O my fatherland), as, in solitude, her voice in dialogue with a delicate oboe solo, she conjures in her mind the image of her beautiful lost land.

The second theme, which one might call Aida's master theme, since it structures the destinies of all the main characters, is that of the tragic conflict of loyalties that war so often causes, if one happens to care about a person or people on the other side. Greek tragedy, as Verdi would have known well, dwells obsessively on these conflicts of "right with right," in which there is no course of action that is not fraught with horror and betrayal. And Aida is, at its heart, a Greek tragedy. Aida and Radamès both face painful conflicts between love and national loyalty, and on both sides of these conflicts loom terrible wrongdoing. Amneris's conflict is less obvious, but by the final act her genuine love for Radamès pits her against the Priests, harsh arbiters of his fate, leading her into a kind of betrayal of her national cause, since Radamès really is a traitor, albeit an accidental one.

Lyric's 1965 production of Aida featuring Leontyne Price (Aida), Giorgio Lamberti (Radamès), Ettore Bastianini (Amonasro), and Fiorenza Cossotto (Amneris).

These conflicts pervade and shape the entire opera, and Verdi, writing with unparalleled daring, gives them unforgettable musical shape. Aida's long first-act aria "Ritorna vincitor" ("Return a victor") searingly depicts the pain of realizing, suddenly, that your heart and mind are torn in two and that you are forced to betray someone you love whatever you do or say. Aida hears the wish for Radamès's victory pass her lips — almost against her intentions — and then says, "the impious words came out of my mouth." Realizing that she is wishing for the defeat of her father and her brothers, she then asks the gods to take away her horrible words and bring about the destruction of the enemies of her people. And hearing herself say that, she recoils again: "Unhappy woman, what did I just say?"

Recalling the beauty of her love, she realizes that she cannot wish death upon the man she loves so deeply. As a sense of moral panic grips her tight, the music, more and more hysterical, expresses her terrible torment: "The sacred names 'father,' 'lover,' I cannot mention or recall. Confused, trembling, for the one, for the other, I would weep, I would pray. But my prayers turn to curses, weeping is a crime, and sighs are guilty..."

This is what war does to people who love. And this is the real theme of Aida. For the hideous predicaments created for decent people by this cycle of retributive wars there is but one remedy, and it is named by Amneris at the opera's end, as she addresses the god Isis: "Peace, I implore you, peace, peace, peace." Great nations have yet to find this solution.

Martha C. Nussbaum is Ernst Freund Distinguished Service Professor at the University of Chicago, appointed in the Law School and the Philosophy Department. Her The Tenderness of Silent Minds: Britten and his War Requiem will appear from Oxford next fall.