January 08, 2024

First the music

by Justin Vickers

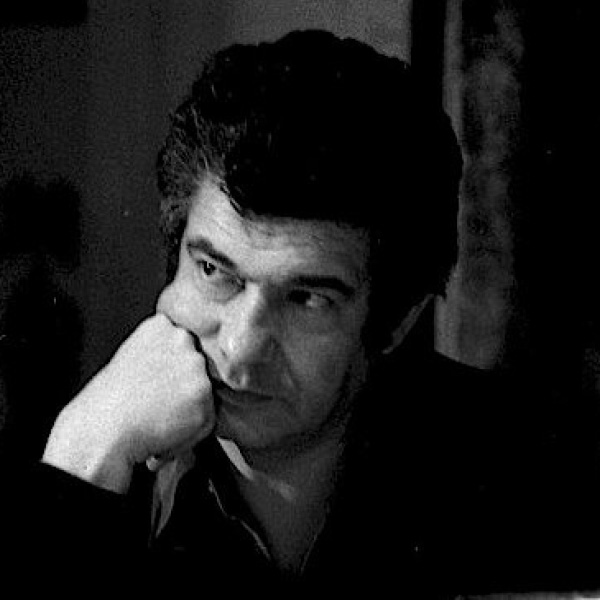

Primarily owing to his utter devotion to the musical score, the French opera director Jean-Pierre Ponnelle (1932–1988) ascended to the highest echelon of his craft. This fidelity was his answer to the age-old operatic debate central to Richard Strauss's Capriccio (1942), derived from the title of an opera by Antonio Salieri: Prima la musica e poi le parole, or, "First the music and then the words." Ponnelle believed anything a designer or director could require was contained in the work of the composer and librettist. Especially later in his career, working as both director and designer, his productions — from the costumes and stage direction to the set pieces and lighting schemes — reflected his radical, focused attention on the source material.

Ponnelle's vision for his creations transcended the size or style of the individual operas themselves. Whether in Wagner's all-encompassing stage works, Mozart's opera seria or comedies, or even 20th-century masterworks from Berg and Schönberg, Ponnelle immersed himself in his uncompromising conceptions. The results of these "whole world creations" elicited both glowing praise and purist disdain — but the mark he made on the discipline as director-designer is unmistakable and extends well into the 21st century. His productions were and still are welcomed onto the stages of the world's greatest opera houses.

Among his most beloved is La Cenerentola, a 1969 commission for San Francisco Opera under its longtime General Director Kurt Herbert Adler (1905–1988). The work provides an immediate glimpse of quintessentially Ponnellian attributes. Two-dimensional scenery evokes the muted hues of 19th-century postcards, against which the colors of his costume designs form striking contrasts (or blend intentionally into the setting), while the lighting thoughtfully focuses rather than disperses our attention. Every element on the stage is intended to amplify the music.

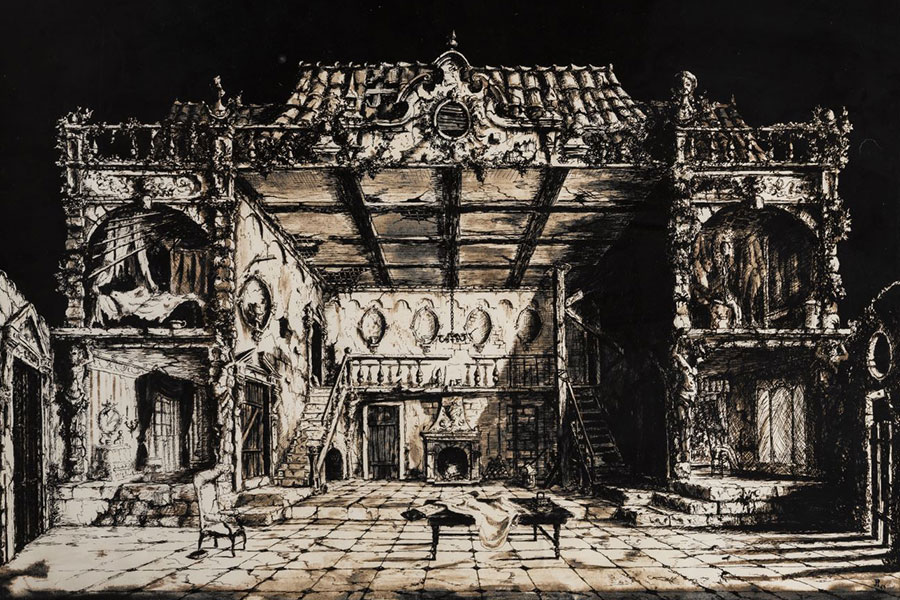

A 1969 sketch by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle for Don Magnifico's home.

As a young music student in the Conservatoire de Paris, Ponnelle additionally studied painting (briefly at the Sorbonne with cubist Fernand Léger). It was this latter skill that brought him to the attention of composer Hans Werner Henze, and the composer's invitation for Ponnelle to design the sets and costumes for his two new ballets in Wiesbaden, Jack Pudding (1950) and Anrufung Apolls (1951). The following year, Ponnelle designed Henze's first opera, the twelve-tone Boulevard Solitude (itself a reconceived one-act Manon Lescaut set in postwar Paris). Ponnelle's designs for the opera were inspired by the Bauhaus movement established in 1919 Weimar, with clean lines, established rectilinear shapes, and stylized forms.

Ponnelle made his American debut under Adler's invitation in the late 1950s, designing Carl Orff's Die Kluge and Carmina Burana, and the following season he was commissioned to design the American premiere of Richard Strauss's Die Frau ohne Schatten (the composer was a family friend of the Ponnelles). These early works from Ponnelle as designer — heavily influenced by his previous training as a painter — are awash with vivid color and audacious designs, a far cry from the productions that would follow. Adler had seen something brilliant in the early work that he was invested in cultivating and encouraging.

Ponnelle acknowledged several individuals as the inspiration for his approach, including actor-turned-director Carl Ebert (a co-creator of the Glyndebourne Festival Opera), with whom Ponnelle worked in 1950s Berlin. Ebert impressed upon the young Ponnelle that he should "read a musical score with the eyes of a director." Together with the specific stage lighting and scenic theories of Adolphe Appia (1862–1928) — who espoused the ineluctable significance of unity between the director and the designer — Ponnelle formed his own musico-directorial practice.

In what was an organic and gradual evolution — certainly informed from his work with spoken theater — Ponnelle followed a prescriptive methodology of his own devising. This began with the music. In an Opera Quarterly interview three years before his untimely death, Ponnelle described his process: "I cannot think before I know the score perfectly, I cannot. Not only the piano score: I prefer to work with the full orchestral score... For me, all the information comes from the music. After that follows dramaturgical analysis, trying to discover the relationships between the characters... When the musical score and the analysis of the libretto are ready, I see my mise-en-scène clearly, automatically."

He eventually assumed the role of director and designer for all his projects, a dual capacity that facilitated and even necessitated close association with the conductors of his productions. He was a frequent collaborator with Claudio Abbado, Herbert von Karajan, and Nikolaus Harnoncourt, among others. "A conversation with him about a score," remarked the German conductor Wolfgang Sawallisch, who conducted Ponnelle's productions of Hindemith's Cardillac and Strauss's Die Frau ohne Schatten, "was a genuine dialogue."

Jean-Pierre Ponnelle

When Ponnelle returned to San Francisco Opera in 1969, the Cinderella he premiered there embodied his evolved sensibilities. He determined that his own earlier works had relied too much on raucous amalgams of color. (His 1967 production of Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia for the Salzburg Festival revealed his new moderation and focused discipline.) Critics came to describe the approach as "anti-color"; he would counter by articulating color's critical importance. "Onstage everything is a symbol," he said. "Color takes on a dramaturgical significance... I use color to enhance the drama of a piece." His embrace of an achromatic mise-en-scène spoke to his desire that the characters and their music — the essence of the world evoked by the full orchestral score — be experienced by the audience first and not explicitly through visual extravaganzas.

Of his initial conception for La Cenerentola, Ponnelle declared that it ought to conjure "the naïve quality of some Italian sketches from the Biedermeier period, 1820-30 — that kind of milieu — a picture postcard out of the past." Such a setting departs from the world of the fairy tale and its numerous early iterations, placing it closer to the era of its composer, Gioachino Rossini (1792–1868). His detailed conceptions of the composer's comic characters' attire and overstated gestures position them, as the German press concluded with the 1981 Munich production, within the "brilliant commedia dell'arte" tradition.

The balance achieved between bleakness and humor is a hallmark of Ponnelle's concept of La Cenerentola. When Alidoro — the opera's surrogate for the Fairy Godmother — enters the stage as narrator and enchants the theater's curtain to rise, this two-dimensional world is magically revealed. The set designs recall 18th-century tunnel books, predecessors to contemporary three-dimensional pop-up books, a view into which the audience has the perfect perspective. The façade of Don Magnifico's once-great home appears as a sequence of cut-outs and engravings with a central hallway and dilapidated staircases between two adjacent rooms upstairs and alongside the hall.

The reference to postcards is also met out in the layered effects of multiple proscenium arches in Don Ramiro's palace. The first downstage arch is the most visible to the audience and is decorated in rich rococo imagery, while those receding further upstage evince pen and ink sketches of the 18th century.

The characters' costumes in Magnifico's home are in no way a reflection of the high society to which they aspire, subsumed instead in dull tones with hints of the garish but tattered pink and pale blues worn by Clorinda and Tisbe. When vivid colors break Ponnelle's otherwise fixed, selective color palette — a directorial theory he described more than once in interviews — the contrast renders a staggering effect. The brilliant red hunting jackets of Prince Ramiro's courtiers, arriving with the invitation to the palace ball, provide counterpoint to the monotony of Magnifico's residence. The drab taupes and browns of Angelina's attire in her father's home disappear at once from our mind when she enters the Prince's palace in a long black and silver-trimmed ball gown, galvanizing a connection with Don Ramiro's regal evening attire. In their beribboned Biedermeier excess, the stepsisters are a clear foil to Angelina and the Prince. In the opera's finale, Ponnelle reintroduces the stepsisters and their father dressed in grey attire, suggesting an air of repentance, an appropriate binary to the dazzling white wedding dress worn by Angelina, which evokes the ballgown in which the Prince previously beheld her.

Ugo Benelli as Don Ramiro and Frederica von Stade as Angelina in San Francisco Opera's 1974 production of Rossini's La Cenerentola.

Ponnelle did not stop with the fusion of the scenery and costumes in representing Rossini's masterpiece. The elegant, stylized grace and romance between Angelina and Prince Ramiro stands in stark relief to the exaggerated comedic roles in the opera — Don Magnifico and his daughters — whose obvious (albeit thoughtfully choreographed) physical humor derives from the music itself. It is evident that while Angelina's stepsisters and Ugo Benelli as Don Ramiro and Frederica von Stade as Angelina in San Francisco Opera's 1974 production. Carolyn Mason Jones27 | Lyric Opera of Chicago their father might ridicule her as a matter of course, she is not the victim of physical cruelty. Ponnelle derived this from his careful study of Rossini's music. Musicologist and theater scholar Kristina Bendikas notes that if there were physical abuse of Angelina, it "would have broken the safety of the comic condition accepted by the audience" as the premise for the comedy they were observing.

Equally compelling scenes between Don Magnifico and his daughters portray Ponnelle's reading of the musical text, notably when the father is awakened from his unfinished dream and threatens to throw his chamber pot on the two but instead throws a pillow (which, moments later, he cradles like a baby). All of the action of the ensuing scene is perfectly aligned with Rossini's rambunctious score, its levels permitting the appearance of spontaneous improvisations from Don Magnifico.

Another choice example occurs at Dandini's entrance, as the courtiers literally roll out the red carpet in perfect time with the music (when, of course, Dandini is disguised as the Prince). The sisters' behavior and their introductions reveal their true nature — and the comedic roles they serve in the opera — and, per Ponnelle's theories of his own role, are all revealed by the composer. For instance, whereas the stepsisters of Brothers Grimm are "beautiful of face, but vile and black of heart," the musical world of Rossini's stepsisters, sidestepping the fairy tale, portrays a general foolishness and musical arguments between them, but never approaches anything close to vileness. Ponnelle creates a relatable humanity for them, not caricatures, reiterating his signal prioritization: directors must fully integrate the music and its subject as the sole inspiration for visual realization. "Only in this way," Ponnelle affirmed, "can musical reality become theatrical reality and re-establish the original text-music balance — because the mise-en-scène, the movement, then derives from the reading of the score."

La Cenerentola was Ponnelle's most successful and widely-viewed production during his lifetime, among a career marked by rich achievements and extensive variety. For a director who unselfconsciously wrote: "I do not work for the so-called posterity," this revival of the 1969 production at Lyric nevertheless speaks to the timelessness and value of Ponnelle's creations.

Dr. Justin Vickers was recently named Distinguished Professor of Music at Illinois State University. He is currently writing The Aldeburgh Festival: A History of the Britten and Pears Era, 1948–1986 (Boydell Press) and editing Childhood and the Operatic Imaginary since 1900 (Oxford University Press).