November 06, 2024

Staging Justice

The groundbreaking Blue brings the contemporary lived experience of Black citizens onto the opera stage.

There is something almost magical about the opera Blue. Straddling many edges of genre, style, and form, it is a dramatic theatrical piece that works with the expansiveness of opera as well as conveying the immediacy of musical theater. Blue connects to a rooted moment in time — the present-day of its composition in 2019. In many ways, this story about family and the undisputed horror of losing a child to a violent death gets to the root of the worst fears uniting our experiences across nation, race, ethnicity, and time period. Yet very specifically this story captures the essence of past conflicts involving Black people in the United States. Blue delineates a space where modern policing extends back to patrolling enslaved bodies, the legacy of Emmett Till, and the highly visible police killings of many unarmed Black people since Trayvon Martin in 2012.

Presciently, this opera preceded the murder of George Floyd by a year. The specifics of this 21st-century story encompass what has become a transcending universal truth of oppression for Black people in America. The intimacy of this family’s situation presents both a private as well as an epic portrayal of life in operatic dimensions.

In the first scene, where we meet The Mother telling her three Girlfriends about her recent marriage and pregnancy, we witness an event that feels normal and natural. Here we have an every-woman, called “The Mother” in the libretto, sharing joyous everyday details of young adulthood: getting married and starting a family. Yet this is an extraordinary occurrence — indeed, this is the magic. For this is what had been missing in mainstream opera, a space that had not previously included stories of Black characters who are fully human and relatable to all audiences. Blue showcases Black experiences on the opera stage in a manner that brings a shadow culture of Black operas, operas that have previously been hidden from the majority, into the foreground.

Such Black creative expressions include numerous operas written from the late 19th century up into the present day, works that reveal a deep engagement and care in representation absent in the dominant culture and brings Black perspectives and experiences to the forefront. This shadow culture includes Black singers who sang operatic arias, primarily in recitals (including Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, Thomas Bowers, and Sissieretta Jones in the 19th century); Black opera companies (such as those run by Theodore Drury and Mary Cardwell Dawson); and the works of Black composers (including Harry Lawrence Freeman, Shirley Graham DuBois, William Grant Still, Nkeiru Okoye, Anthony Davis, and many more).

Blue belongs to two intersecting trios. The first trio is delineated by the momentous summer of 2019, when three Black operas began to make history. Composer Anthony Davis and librettist Richard Wesley’s The Central Park Five premiered at Long Beach Opera in June 2019 and went on to be the first opera by a Black composer to win the Pulitzer Prize for Music (Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels’s Omar was the second, in 2023.)

Fire Shut Up in My Bones, with music by Terence Blanchard and libretto by Kasi Lemmons, premiered at the Opera Theatre of Saint Louis the very same week. Originally commissioned by Washington National Opera’s Timothy O’Leary, who had previously served as General Director of Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, Fire Shut Up in My Bones went on to be the first opera by a Black composer presented at the Metropolitan Opera in its history (the company began in 1883). Such an occasion, 66 years after Marian Anderson’s historical debut at the Met, has begun to act as a similar beacon to other opera houses to perform and commission operas by Black composers. (Lyric, a co-producer, presented Fire to great acclaim in its 2021/22 Season).

This brings us to Blue, which premiered at The Glimmerglass Festival in July 2019, won the Music Critics Association of North America 2020 Award for Best New Opera, and was the first of this trio to have a commercial recording available.

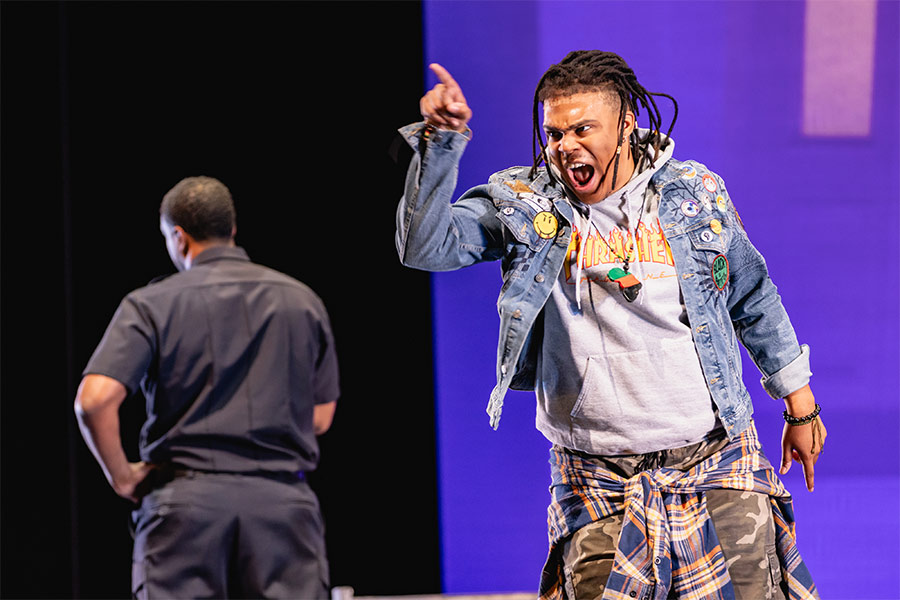

The opera is rich with depictions of complex family relationships, as with The Father and Son.

The second trio of which Blue is a member resides in the work of composer Jeanine Tesori; it is her third opera. Tesori’s first two operas were also commissioned by forward-looking opera director Francesca Zambello, former General Director of The Glimmerglass Festival and current Artistic Director at Washington National Opera at the Kennedy Center. Tesori’s fourth opera, Grounded, a collaboration with playwright, now librettist, George Brant, opened the 2024/25 Season at the Metropolitan Opera.

Opera is an important part of Tesori’s polyphonic voice as a composer. Her training as a pianist began in finding tunes on the keyboard at age three; she became a serious classical musician in her teens, then switched from pre-med to a music major at Barnard College. She worked for 15 years as a gigging musician in Nashville, learning from Buryl Red (who had studied with Elliott Carter at Yale) and taking inspiration from Leoš Janáček, Béla Bartók, and Tania León, composers whose work spans classical art music shaped by folk rhythms, melodies, and structures from Eastern Europe and Cuba.

Many of Tesori’s recent projects have given voice to experiences outside of her own identity. One of her best known and most celebrated works is the musical Fun Home (2013), based on the graphic memoir by Alison Bechdel that centers on the discovery of queer sexual identities and the pain of losing a loved one to suicide. Caroline, or Change (2003), Tesori’s first collaboration with Tony Kushner (who later wrote the libretto to her first opera), is about a Black maid who works for a Jewish family in 1963 Louisiana, and engages the early Civil Rights movement through spirituals, the Blues, Motown, and Klezmer music. Soft Power (2018), her collaboration with David Henry Hwang, reverses the lens from The King and I by exoticizing America through a Chinese musical, set in the future, that challenges the nature of democracy, cultural identity, and racism. Soon after Blue, Tesori was the Supervising Vocal Producer for Steven Spielberg’s movie version of West Side Story (2021), a work about class, racial ethnicity, and Puerto Rican life in Manhattan’s Upper West Side in the late 1950s.

Blue brought Jeanine Tesori and Tazewell Thompson together. Commissioned for The Glimmerglass Festival, an early impetus for the opera’s story was Zambello’s question, “Why is the killing of innocent Black men happening all the time, and how can we use art to speak and ask the question?” Writing his first libretto, Thompson carried years of experience from spoken theater as an award-winning playwright and director, along with his deep knowledge as an opera director. Thompson’s new opera, Jubilee, recently premiered at Seattle Opera.

The Father, here with his fellow policemen, is a so-called “Black in blue.”

Tesori has spoken of her role as a white woman collaborating with a Black man in this work about police violence in today’s political climate: “For me, Tazewell has the underlying rights to this story because it is so connected to his experience in the world… . That to me is what reparations look like. It is to acknowledge that that story does not belong to me. I participate, but Tazewell has the underlying rights. That acknowledgment is really important.” She moves thoughtfully in these spaces, joining this conversation with energy and “with a lot of humility.”

Sometimes, she says, “I feel scared, I feel uncomfortable — but I don’t feel like exiting. And that staying in, to me, is the invitation to be in specific dialogue.” She continues, “I know that it is my responsibility to go deep or don’t go. So, if I’m going to be writing in a community, I better know as much as I can possibly know, without truly knowing with a big ‘K’. Otherwise, I should stay out.”

The musical language and style of Blue reflect a deep contemporaneousness. The dramatic pacing expands and unfolds in a way that comes alive and is enriched by the vast architectural acoustics of the opera house yet also has a profound intimacy, the direct impact of watching the conversation up close. Narrative and musical themes recur not just as quick references, but as embedded tropes that weave sections of the opera together. The first half of the opera opens up in scene one with The Mother and her three Girlfriends. These women feel like people one might know, as they chide, trade jovial banter, and, when necessary, express their apprehension with drop-dead seriousness. At the end of the scene, despite their concerns about the difficulty of keeping a Black boy safe in today’s America, they pledge unwavering support and love.

In the middle of this opening exposition, we get to know The Mother in her aria “Go Figure,” which gets to the core of who these women are. She has fallen for a man with “big hands,” a “big heart,” “big ideas,” and a “big love” that makes her pause. She stops in her tracks when she says, almost as an afterthought as though she still cannot really believe it, “Go figure.” The pause and falling major third in the orchestra that opens this aria and continues throughout this expressive reflection add a shimmer to this moment and its return several times in Act One. This wistful lyrical gesture, the pause and descending third, brings these women to life and helps us in the audience understand their vulnerable existence while also experiencing the mystery and joy in this moment.

The Father and Mother wrestle with grief.

The midpoint of the opera, the heroic duet between The Father and The Reverend that opens Act Two, is weighted down by two deep basses who narrate the events that happened after Act One, and the devastating reality that now faces the young family and their community that we have grown to care so much about. The somber heaviness of two men encountering the clash between the misuse of the authority of the state (through a deadly mistake by the police) and the ineffective consolation of the church are reminiscent of the oppressively fraught duet between King Philip II of Spain and the Grand Inquisitor in Verdi’s Don Carlos. The dark moods contrast between these two operas as the leaders in Don Carlos rashly bargain murder and sacrifice for their own corrupt gain. In Blue the men are the victims, not the perpetrators, of a gross injustice; both suffer from systemic wrongs.

In a momentous groundswell of pain, the “Lay my burden down” theme is first introduced briefly in the duet between The Father and The Reverend. This theme becomes the connective tissue for the second act and Epilogue. As the pause and falling third of wonder and anticipation were woven throughout the first half, the descending “Lay my burden down” theme feels at once recognizable and familiar as it unites the second half of the opera. It becomes the culmination of the funeral service at the end of Act Two, and the point in the Epilogue when you realize that the joy of a shared family dinner will never happen again.

The Reverend consoles the community.

Historically and musically, Blue compassionately tells a story that is at once painful and identifiable to so many of us. Through the collaboration of an interracial compositional team, this opera offers a microcosm for listening to, and learning across, diverse vantage points and lived narratives. While Blue is not the only opera about Black experiences, it is part of a new era of Black operas in the United States that extends back to the 19th century and carries on to the present. The luster of this current golden age of Black operas is not due to the paucity of operas written before, but to the fact that new operas are joining earlier works that are finally emerging from the shadows and challenging the elitist reputation of opera as a genre. The presentation of Black lives in ways that reveal a three-dimensional humanity is appearing in an unlikely, yet increasingly emblematic place: opera. And the opera house is becoming an eloquent stage for a trenchant social justice.

Naomi André is the David G. Frey Distinguished Professor in the Department of Music at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Professor Emerita at the University of Michigan.

Adapted from liner notes for the Washington National Opera recording of Blue (Pentatone).