January 07, 2024

Taking a solo

To compose Champion, Terence Blanchard knew he’d have to rely on his own individual sensibilities.

Terence Blanchard grew up with the sound of opera in his ears — his father was an amateur baritone — but he gravitated toward jazz early on. "Obviously, [opera] became a part of my musical DNA without me even knowing it," he says.

Blanchard's storied jazz career has brought him seven Grammy awards and two Oscar nominations and has placed him at the pinnacle in that genre for decades. Now his operatic credentials are catching up. His surging, pulsing, dynamic score for Champion has won fans from St. Louis to San Francisco to New York. His second effort, Fire Shut Up in My Bones, which opened the Metropolitan Opera's season in 2021 and arrived at Lyric in 2022, was hailed by The New York Times as "bold and affecting" and roundly praised by audiences. The composer of these two instant classics seems as surprised as anyone by their success.

"When Jim Robinson from Opera Theatre of Saint Louis contacted me and told me they were thinking about asking me to do an opera, man, I thought he was nuts," he chuckles. "But they stepped me through the process. It was a beautiful experience."

Blanchard has been overwhelmed by the response to his work. "I thought I might be run out of town," he says, laughing. "The world of opera can be very intimidating. I was very prepared to have my excuse of, 'Well, I'm just a jazz musician.' I'm listening to all these classic operas, going, 'How did he do that? That's not me.' My composition teacher, Roger Dickerson, kept saying, 'Don't think about writing opera — just tell a story.' Once he told me that, I thought, 'I've got to have a don't-care attitude and just do what I feel is right. If it works, it works, and if it doesn't, I still have my career.'"

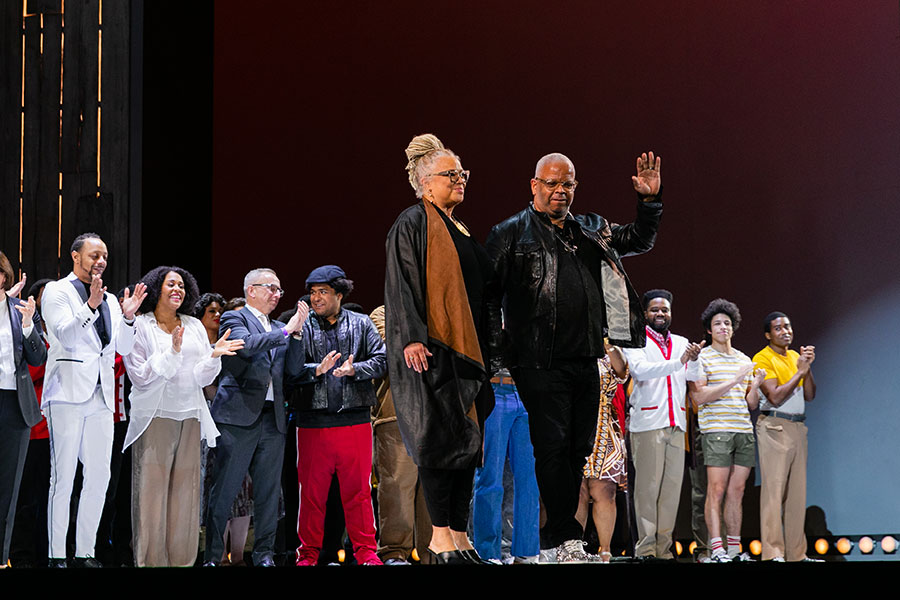

Composer Terence Blanchard takes a bow alongside librettist Kasi Lemons on the opening night of Fire Shut Up in My Bones at Lyric Opera of Chicago (2021/22 Season).

"When I became a jazz musician," he adds, "I wanted to be Miles Davis. I'd try to play like him, and when I got a cold, I just loved that my voice was hoarse. But once I met Miles Davis, I realized that's why his music sounds like it does. So what does that mean for me? That started me on the search to try to find out what it is that I like. You have to be comfortable with who you are as a musician."

Blanchard's operas share a common theme of central characters struggling to come to terms with their identity in a hostile world. "When you think about intolerance and bigotry, it's a similar thing," he says. "Everybody's trying to just be loved and be respected. It's always amazing to me that we can have people who consider themselves Christian but don't do Christlike things. It's not necessarily about being gay — it's more about injustice and intolerance. That's one of the reasons why I kept saying, 'I can't be a token; I have to be a turnkey.' Because there are so many other stories, so many different cultures, so many different ethnic groups that have been underrepresented in the operatic world, and we have to open ourselves up to all of those possibilities."

The Met premiere of Fire Shut Up in My Bones marked the first time an opera by a Black composer was performed at that storied house. (At Lyric, it was just the second.) "There were mixed emotions," says Blanchard of his opening-night curtain call. "I posted some photos on my Instagram of my teacher Roger Dickerson, with his teacher, Howard Swanson, and one of his colleagues, Hale Smith — three great Black composers that nobody knows. Prior to going to the Met, I heard Highway One, by William Grant Still, down in Saint Louis. Didn't know it was William Grant Still and kept thinking, 'Whose music is this? This is good!' Next thing, I'm at the Met — I think I was doing an interview for CBS — and they brought out a ledger that showed all the operas by Black composers who had been refused or rejected, and William Grant Still's name was in there three times. It blew me away. It's an amazing thing to be the first, but the thing I always say is I was never the first who qualified. There were many composers who were much more qualified than me but just didn't get the opportunity."

Blanchard is thrilled to be back at Lyric Opera. "Oh man, I love that place!" he says. "I love the sound of the hall. I love everything about it. I just wish they would do my productions in summertime, you know?" he adds with a laugh. "It's cold, man. I'm a Southern guy."

Blanchard is a strong believer in the power of art to move souls. He also believes in the power of new work to create new audiences. "I think what's been interesting about what's happened to me is that I've been bringing new people in," he says. "That's been something exciting to see. I remember when we did Fire in Chicago, there were a lot of people who would come up to me and tell me it was the first time they had gone to Lyric to see an opera. Hopefully it opened up possibilities of seeing other productions."

Louise T. Guinther, longtime senior editor at Opera News magazine, is an arts writer based in New York.