April 17, 2023

Hot and cool: The creation of West Side Story

The 1958 Tony Awards included five Best Musical nominees. Three of those shows — seldom, if ever, performed today — were memorable chiefly as vehicles for major stars: Tony Randall (Oh, Captain!), Lena Horne (Jamaica), and Gwen Verdon (New Girl in Town). The fourth show, The Music Man, which ultimately won the award, was an affectionate depiction of turn-of-the century Iowa that turned journeyman actor Robert Preston into a Broadway headliner. The fifth nominee was the "odd show out." To begin with, the principals were unknowns, not stars. It was a gritty show, colored by both the cruelty and the ecstasy of young people living and loving in a vibrant but dangerous urban setting. It also had a tragic ending, unprecedented for a Broadway musical. But it abounded with awe-inspiring talent, and everything about it communicated the excitement of the new.

This was West Side Story.

The first Maria, Carol Lawrence, and the first Tony, Larry Kert, on location in New York City (West 56th Street between 9th and 10th Avenue) for a West Side Story publicity shoot.

The show's many miracles began with its creators, as formidable a team as any musical-theater production has ever seen. Leonard Bernstein (music), Arthur Laurents (book), and Jerome Robbins (director/ choreographer) had all triumphed on Broadway before. Stephen Sondheim (lyrics), then only 25 years old, was working on his first Broadway show, although he was certainly as acutely intelligent and stupendously gifted as his three colleagues. But however savvy each man may have been, in this case they were all very much feeling their way into a show unlike anything seen previously on Broadway.

On January 6, 1949, Bernstein wrote that Robbins had called him with "a noble idea": a contemporary Romeo and Juliet, refashioned as a conflict between Jews and Irish Catholics, "set in slums at the coincidence of Easter-Passover celebrations" on New York's Lower East Side (the title, in fact, was originally East Side Story). Robbins proposed Laurents as the right person to create the adaptation. But those three were among the busiest people on the American performing-arts scene, and the project was eventually shelved. In 1955, however, when Bernstein encountered Laurents in California, it came up again. The idea of a Jewish/Catholic Romeo and Juliet was now abandoned, in favor of an "American" gang (the Jets) vs. a Puerto Rican one (the Sharks). And so to work, with Sondheim now on board as the fourth collaborator.

Known as a playwright, director, and screenwriter, Laurents later described his West Side Story dialogue as "my translation of adolescent street talk into theater: it may sound real, but it isn't." In his brilliantly constructed libretto, several situations parallel Shakespeare's play:

- the Capulet/Montague ball becomes the "Dance at the Gym," where Tony and Maria meet;

- the equivalent of Shakespeare's "balcony scene" happens on a fire escape;

- although the lovers don't have a modern-day Friar Laurence to marry them, they do exchange vows on their own in the bridal shop where Maria works;

- a confrontation between the gangs results in their leaders' deaths: Riff (counterpart of Shakespeare's Mercutio) is killed by Bernardo (Tybalt), Maria's brother, and the enraged Tony (Romeo) – who'd formerly been a member of the Jets – kills Bernardo.

Laurents's ending departs from Shakespeare, which must have stunned 1950s audiences, accustomed in musicals to seeing conflicts happily resolved in time for the finale. Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet both commit suicide, but in West Side Story only Tony dies – shot by Chino, Bernardo's vengeful friend. The gang members are bitterly castigated by Maria, who accuses them all of Tony's murder. It's clear that their feud has now ended, but one wonders whether the young but disillusioned and emotionally scarred Maria will ever find love again.

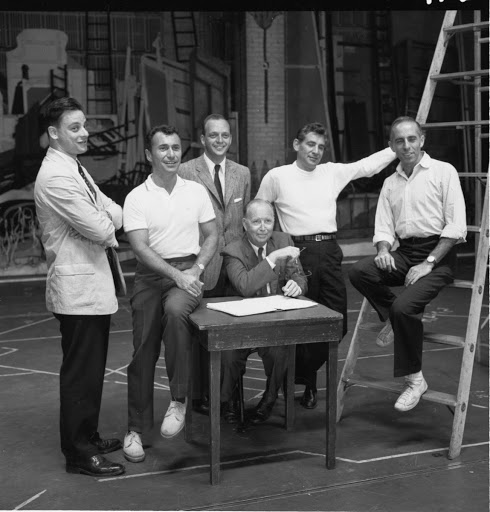

In rehearsal for the first production of West Side Story: left to right, lyricist Stephen Sondheim, librettist Arthur Laurents, co-producer Harold Prince, co-producer Robert E. Grith (seated), composer Leonard Bernstein, and director/choreographer Jerome Robbins.

The show progresses seamlessly from one scene to the next, with five extended dance sequences beautifully integrated into the drama. The dances begin with the young men of the Prologue; with both arms and one leg outstretched as they strut down a New York street, they present one of the most recognizable images from any American musical. Created by Robbins (with the great show dancer Peter Gennaro as his uncredited co-choreographer), the original West Side Story choreography remains enthralling today, whether the Jets, the Sharks, and their girlfriends mambo-ing in an explosion of incendiary sexual electricity in "The Dance at the Gym"; Anita and her cheeky sidekicks in "America" (Bernstein, inspired by a particular Mexican folk dance, marked the music "tempo di huapango"); Riff urging his anxious Jet buddies to stay "Cool," in the show's most overtly jazzy number; and the touching ballet that leads into "Somewhere," midway in Act Two.

Bernstein's universally beloved score is arguably the greatest of his career. Early in the show, breathless alterations between hushed eagerness and all-out exuberance support Tony's premonition that "something's coming." Later, his joyous repetitions of his new love's name ("Maria") illuminate that name through the melodic line's eloquent use of the tritone. The Latin rhythms of Maria's "I Feel Pretty" sparkle, the ideal expression of her irresistible girlishness. The audience follows her star-crossed romance with Tony from the delicate, luminous cha-cha in the orchestra accompanying their first dance to the combination of impetuosity and tenderness in "Tonight," the quiet serenity of "One Hand, One Heart," and the lovers' desperate, anguished phrases preceding the "Somewhere" ballet (the song itself, assigned in the original production to Consuelo, one of the Shark girls, is sung by Maria in Lyric's production.)

In the wild flamboyance of "America" we're captivated by the worldly, deliciously sarcastic Anita. Later, after Bernardo — who had been her fiancé — is killed by Tony, Anita berates Maria in the scathing "A Boy Like That" (to which Maria responds with sweet restraint in "I Have a Love"). Bernardo has no song of his own, but Riff dominates both the "Jets' Song" and "Cool." Together those numbers depict a fearless, charismatic troublemaker who gives new meaning to the adjective "streetwise." Midway in Act Two, the Jets — now without their murdered leader — provide the show's only episode of genuine hilarity in "Gee, Officer Krupke," their endearingly obnoxious justification of their own delinquency.

Bernstein had no objection to opera (he'd written a successful one, Trouble in Tahiti, just five years earlier), but a purely operatic West Side Story wasn't his aim, as he admitted when summing up the challenge facing him and his colleagues:

Chief problem: to tread the fine line between opera and Broadway, between realism and poetry, ballet and "just dancing," abstract and representational. Avoid being "messagy." The line is there, but it's very fine, and sometimes takes a lot of peering around to discern it.

Although he did impose certain rhythmically complicated musical structures on a musically and vocally inexperienced cast (as in the electrifying quintet reprise of "Tonight"), Bernstein took pains to create a score that would be technically manageable and wouldn't tempt his singers into overtly operatic expression.

"I Feel Pretty": Stephen Sondheim (at the piano) and Leonard Bernstein rehearsing Carol Lawrence (Maria, far right) and the ensemble of Shark girls.

The casting process proved challenging. There was none of Broadway musicals' usual "dancing chorus" and "singing chorus"; everyone needed to act the dialogue convincingly, master the music and lyrics, and dance the extraordinary new stylistic fusion developed by Robbins. Grover Dale, who created the role of Snowboy, noted years later that "one of the most amazing things about the choreography is that it starts in naturalism and within seconds naturalism is transformed into a form of ballet and jazz. Making that transition, finding dancers who are capable of doing that, was one of the main casting elements as that show got produced."

The rehearsal period was immensely exciting, if also unnerving, thanks to Robbins, an almost terrifyingly strict taskmaster in preparing the dances. He also wanted tension and competition between Jets and Sharks, insisting not only that they avoid socializing together, but that they rehearse in different rooms! For Chita Rivera, a stunning dancer and the first Anita, it wasn't just Robbins's work on the show that made a lifelong impact on her — it was Bernstein's as well:

It was great to walk into that rehearsal hall and hear that music. When I heard the cha-cha, I couldn't stop crying, it was so perfect for the scene, perfect for the book, and beautiful to listen to. My heart was totally involved with his music. He gave me the library that's in my head of knowing what a wonderful score is all about. Smart and musical and complicated and passionate scores, where the lyrics work beautifully with the music and you can leave the theater humming a beautiful melody.

As for Stephen Sondheim, West Side Story is hardly a favorite among his own works. Five decades after the premiere, he declared with typical frankness: "there aren't any fantastic rhymes in West Side Story. They're almost all day and may, go and show. It would have been betraying the characters if they'd rhymed too well. 'I Feel Pretty' still bothers me. It's just too elegant for a girl like Maria to sing. I mean, "It's alarming how charming I feel"? That wouldn't be unwelcome in Noël Coward's living room."

But Sondheim has never denied the show's uniqueness, noting that "its importance lies in its theatricality. It was a more sophisticated blending of music, dance, song, and dialogue than anything that had been done before."

The creators didn't start out anticipating success; they were simply eager to do something genuinely bold, regardless of the outcome. Having no idea what to expect, everyone involved in the show was consequently astounded on opening night of the Washington tryout, when the audience literally screamed with enthusiasm during the curtain calls. In New York, where West Side Story premiered on September 26, 1957, the most astute critics thoroughly understood the show – especially The New York Times's Brooks Atkinson, who hailed the creative team:

Pooling imagination and virtuosity, they have written a profoundly moving show that is as ugly as the city jungles and also pathetic, tender and forgiving. [Tony and Maria's] balcony scene on the firescape [sic] of a dreary tenement is tender and affecting. From that moment on, West Side Story is an incandescent piece of work that finds odd bits of beauty amid the rubbish of the streets. Everything contributes to the total impression of wildness, ecstasy and anguish.

Choreographer Jerome Robbins leads dance rehearsals with the original cast of West Side Story.

West Side Story is one of the world's most honored and most often performed shows, and exciting productions like Francesca Zambello's — produced at Glimmerglass, Houston, now at Lyric — continue to renew its hold on audiences. Much ink has been spilled in explaining why it remains a seminal work of American musical theater. Among today's commentators on the show, Jamie Bernstein, the composer's daughter, has been particularly eloquent and deserves the last word:

[Bernstein] was somebody who was always trying to make the world a better place. The best vehicle was through his own music. West Side Story was his most successful attempt to use his music to explore the difficulties we all live within our world and to use music as almost a kind of healing process. West Side Story is about hatred, intolerance, fear of strangers arriving in your neighborhood — these are issues as urgent for us today as they were back then. My father's music really gives us a language with which to explore these issues and find ways to resolve them.

This article was originally printed in Lyric's 2018/19 West Side Story program.

Roger Pines, former dramaturg of Lyric Opera of Chicago, has appeared annually on the Metropolitan Opera broadcasts' "Opera Quiz" for the past 17 years. He contributes regularly to opera-related publications and recording companies internationally. This spring he taught a seminar on musical theater for Chicago's Newberry Library and completed his fourth consecutive year teaching the opera repertoire course for Northwestern University's Bienen School of Music.