May 27, 2021

Rusalka and her Journey

After its triumphant 1901 world premiere in Prague, Antonín Dvořák’s Rusalka took most of the twentieth century to find an international audience. This seems nothing short of scandalous — and an absolute deprivation for several generations of operagoers — since the music is some of the most glorious in the repertoire. Fortunately, as singers become increasingly comfortable singing in Czech, Rusalka is now produced more frequently, with a grateful public inevitably asking itself, “Where has this music been all our lives?”

Eric Owens (Vodník) and Ana María Martínez (Rusalka) in Lyric's 2013/14 premiere of Dvořák's opera

Beyond the justly celebrated “Song to the Moon,” the heroine has two other equally memorable arias. There are also magnificent vocal opportunities for the other principals; a devastatingly moving final scene for Rusalka and her prince; rewarding supporting roles; and an orchestral contribution abundant in superb craftsmanship combined with dazzling musical imagination.

Dramatically, too, this opera is exceptional, as was memorably evident at Lyric in the production directed by Sir David McVicar and designed by John Macfarlane (the same team that will be creating Lyric's new production of Macbeth in 2021/22). Rusalka presents what McVicar has described as "a fairytale for adults. While colored by somber and occasionally even sinister qualities, the piece also reveals the essence of romantic longing with rare depth and truthfulness.

It is the central character’s emotional arc that combines with Dvořák’s music to give the work such an immediate appeal. The leading lady of Lyric’s Rusalka, soprano Ana María Martínez, has commented that “of course, the story has to do with love, but it has to do with the journey toward becoming. Rusalka wants to be human and, more than anything, she wants a soul — she’ll sacrifice whatever it takes to have that. The core of this piece is that quest, that desire, that journey.”

When Dvořák’s name is mentioned, audiences think first of symphonic repertoire – this despite the composer’s substantial operatic output. The fact remains, alas, that few of his ten operas have been successfully exported, and only Rusalka has finally established itself in the public’s affection.

The young Dvořák played viola in the orchestra of Prague’s Provisional Theatre, which enabled him to acquire a thorough grounding in operatic repertoire. Once composing his own operas, he worked frequently with libretti that concentrated on country life in Czech villages. The composer was building on the heritage of the most notable Czech stage works (above all those of Smetana, composer of The Bartered Bride). All sorts of “genre” scenes figure in Dvořák’s first four operas, although he looked to historical tales as dramatic sources for three others. He followed Rusalka (1901) with his final stage work, Armida (1904), its legendary characters previously seen in operas of Vivaldi, Handel, Gluck, and Rossini.

Whatever resemblance Rusalka bears to Hans Christian Andersen’s “Little Mermaid” story is evident only in the basic idea of a water creature in love with a human being and her refusal to kill him to end her own suffering. Librettist Jaroslav Kvapil did look to Andersen, while giving attention to tales gathered by two remarkable nineteenth-century Czech writers, Karol Jaromir Erben and Božena Němcová. He also read Friedrich de la Morte Fouqué, the German Romantic writer remembered today chiefly for the fairytale novella Undine (1811), the heroine of which is one of literature’s most celebrated water creatures.

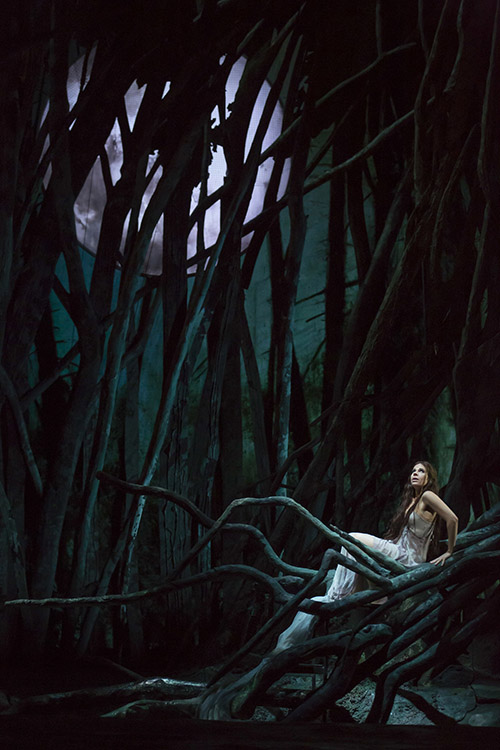

Ana María Martínez (Rusalka) in Sir David McVicar's production for Lyric, designed by John Macfarlane who responsible for Lyric's upcoming production of Macbeth

The “rusalky” of Czech mythology are water nymphs living in the depths of a river or lake. A “rusalka” is an “unquiet dead being” — a young woman who had previously committed suicide after being rejected by her lover. In that respect these creatures resemble the unearthly “wilis” in the ballet Giselle. Where a “wili” literally dances her lover to death, a “rusalka” lures a young man who, in his attempt to pursue her, is drawn into the water only to die in her embrace. Many Rusalka productions place the heroine in a tree for the “Song to the Moon,” which is, in fact, staying true to the mythological figure: although a water creature, the “rusalka” had legs (unlike Andersen’s mermaid), and was apt to spend much of her time climbing onto tree branches to while away the hours singing.

There is another Rusalka (the opera by Alexander Dargomyzhsky, premiered in 1856), and the hapless water nymph has been seen in other incarnations in art, music, dance, and literature. One thinks particularly of what has emerged from German writers and composers — for example, Heinrich Heine’s poem about Lorelei, set by more than 50 Lieder composers; the operas of E.T.A. Hoffmann (1816) and Albert Lortzing (1845), both entitled Undine; the entrancing ballet Ondine (1958), composed by Hans Werner Henze for Dame Margot Fonteyn; and Melusine (1971), a brilliant opera by Aribert Reimann. There have been numerous plays based on Undine (including one by France’s Jean Giraudoux that starred the young Audrey Hepburn on Broadway in 1954). That character was also memorably painted by Turner and Gauguin.

Having written the Rusalka libretto in 1899, Kvapil didn’t have Dvořák at the top of his list of desired collaborators; he showed his text to a number of other composers who expressed no interest. A fortuitously timed press report informed Kvapil that Dvořák was searching for a new libretto, and it was František Adolf Šubert, director of Prague’s National Theatre, who recommended Kvapil to Dvořák.

Ježibaba (Jill Grove) casts the spell to make Rusalka human

Dvořák was apparently inspired by a lake in the small village, southwest of Prague, where he spent summers and holidays. He composed a good deal of music there, including Rusalka (it seems he saw a fairy standing above the lake!). Instantly attracted to Kvapil’s text, he began working on Rusalka in April of 1900. Incredibly, he was already finished with the full score by the end of November the same year. The honor of introducing the work went to Prague’s National Theater, which utilized all of its impressive resources vocally, orchestrally, and scenically, in order to do Rusalka full justice.

Premiered on March 31, 1901, the opera was heard more than 600 times in Prague during the first half-century of its performance history. Internationally there were some important productions, but sporadically: between 1948 and 1993 there were productions in Dresden, London, Vienna, Zürich, San Diego, Munich, London again, and New York. The advocacy of first Renée Fleming and then subsequently Ana María Martínez (both of whom star in hugely acclaimed complete recordings of the opera) has been immeasurably important in confirming Rusalka’s place in the repertoire.

This astounding, richly varied score offers as many memorable highlights as one would find in any of the world’s more popular operas. The Act One prelude introduces the opera’s most important theme — a soulful legato melody associated with the heroine, which returns in all her appearances onstage. The three wood nymphs then introduce themselves in several pages of scintillating three-part harmony, beginning on the nonsense syllables “Hou, hou, hou!” The nymphs return midway in the last act, providing a notable “breather” from the dramatic goings-on elsewhere in the opera. Their languid, rapturously beautiful trio, with its soaring refrain (supported by a shimmering orchestra), makes a genuinely intoxicating impression in any Rusalka performance.

Although, when we first behold them, the wood nymphs are singing about the moon above the lake, and about the Vodník nodding his old greenish head, most of their music requires tremendous high spirits. In contrast the Vodník himself brings with him a decidedly somber vein of expressiveness. When he first confronts his water-nymph daughter Rusalka, her desperate desire for a human soul leaves him appalled. He responds to her yearning phrases with an immensely dramatic declaration punctuated by repetitions of the word “Běda! (“Woe!”) that will be heard from him in all his subsequent appearances. His affection for Rusalka, and his concern for her, will emerge in Act Two with a lulling, lullaby-like, strophic aria, exquisitely hushed and intimate in its mood.

It is her opening scene with Vodník that introduces us to Rusalka, when she’s terribly unhappy and begs to speak with him. Instantly we feel the aching sincerity that is the heart of this extraordinarily touching heroine. Her music can be inward-looking but also warmly expansive, as we hear in the ensuing “Song to the Moon.” Dvořák makes the aria’s simple opening phrases dulcet, before lifting the voice gently into the wonderfully buoyant main theme. A gentle, silky-textured accompaniment immeasurably enhances the aria’s effectiveness (the two verses vary hardly at all up to the final page, where the voice rises gradually to a potentially thrilling sustained high B-flat). It will surprise many listeners to discover that Rusalka has two other superb arias: the one in Act Two is hair-raisingly dramatic, with her declaration that she is neither nymph nor woman, unable to live or die; and in Act Three the central melody is profoundly sad, centered much lower in the voice, expressing a painful despair and resignation to her fate.

Following the “Song to the Moon,” we’re introduced to the forest witch Ježibaba. This hugely rewarding role is a gift for a big personality possessing a dramatic mezzo suited to, say, Azucena in Verdi’s Il trovatore. Ježibaba’s aggressiveness could hardly present a greater contrast with Rusalka’s light, sweet, plaintive phrases. Central to the second half of their first scene together is Ježibaba’s repeated incantation, “Čury mury fuk” (roughly translated as “Abracadabra”), with Dvořák’s delicious touches of cymbals and triangles. Both in this act and in her two appearances in Act Three, the singer portraying Ježibaba must put her characterization across as much through relish of the text as through the role’s imposingly wide vocal range.

The prince — our tenor, naturally — is initially light, lyrical, and captivating. Once Rusalka mysteriously appears before him, his passion for her is instantaneous and his sweet phrases turn more and more grand-scale. By the end of Act One, Dvorák is giving him climaxes of thrilling fervor worthy of Verdi’s Manrico, reaching an apex of excitement with two full-voice high As when he refers to the lovely, wordless young woman before him as “pohádko má,” “my fairytale.”

The final scene: Ana María Martínez (Rusalka) and Brandon Jovanovich (Prince)

The folk-dance element is vivid in Act Two’s brief orchestral introduction, as it also frequently is in the lively dialogue between gamekeeper and kitchen boy (although the kitchen boy turns notably mysterious and intense as he describes the silent Rusalka, with the gamekeeper also taking on a note of mystery in speaking of Ježibaba). Their scene leads directly into the first of two scenes in which the Foreign Princess confronts the Prince and the mute Rusalka. Effectively sung by both dramatic mezzos and sopranos, the Princess can express herself in an exciting style, ultra-energized, driving, and thrustingly powerful.

Act Two also brings us the chorus playing Prince’s guests, and their arrival is presented in some of Dvořák’s most bustling, festive music, followed by a brief but elegant ballet sequence and a buoyant, folk-style chorus. We don’t see the chorus again onstage, but the women are heard offstage in Acts One and Three as Rusalka’s sister nymphs. Especially expressive is their third-act music: they’re heard declaring that Rusalka cannot join in their dancing — they’ll retreat if she comes near them. They anticipate that her only companions will be found among human graves. Their music begins with a cool otherworldliness, but then turns darker and more aggressive as their message to Rusalka becomes more severe.

The final confrontation between the Prince and Rusalka that ends the opera is, quite rightly, the emotional apex of the entire work. It alternates between shattering intimacy — when she asks why he took her in his arms and then lied to her — and heights of almost Tristan-esque ecstasy, with the Prince’s line ascending to high C when he insists that Rusalka kiss him, even if it means his death.

After the Prince floats his dying phrases and the orchestra plays its sad interlude, we hear Rusalka’s last speech. Her wish for God to pardon the Prince is expressed in a mere 60 seconds of music, but what deeply eloquent music it is! She is for eternity in limbo — neither nymph nor human being – but the sheer depth of human emotion emerging in this magnificent passage will leave any listener simply shattered. It is the final evidence of what Ana María Martínez says of this heroine: she represents “absolute, pure love” in everything she says and does. “She takes responsibility for her choices, and always — even in such pain — she stands for love.”

Roger Pines, Lyric Opera’s dramaturg, writes frequently for major opera publications and recording companies internationally.

This article originally appeared in the program of Lyric's 2013/14 production of Rusalka.

Lyric Audio Streaming

Lyric Audio Streaming

Nothing quite compares to the excitement of hearing the biggest stars in the opera world performing with a full orchestra and chorus in front of a live audience. Now you can experience the magnificent sound of full-scale opera free, whenever you like, with Lyric Audio Streaming. Listen to previously recorded full operas online and through a variety of online music streaming platforms.

Header photo: Act Two of Lyric’s production of Rusalka, designed by John Macfarlane

Photos: Robert Kusel and Todd Rosenberg