September 13, 2022

Speaking of Ernani

Lyric began its survey of the early operas of Giuseppe Verdi in the 2019/20 Season with Luisa Miller (1849) and continues now with Ernani (1844), a crucial work in the composer’s development. We arranged for a conversation between Enrique Mazzola, Lyric’s Music Director, and Dr. Naomi Andre, the newly appointed David G. Frey Distinguished Professor in Music at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. Both are renowned aficionados of these works, and they agree: Ernani has tremendous significance — as an exemplar of bel canto style, as a pivotal moment in Verdi’s career, and as a glorious achievement that hints of something larger (and perhaps darker) on the horizon.

While Ernani isn’t performed very often, it has remained in the repertoire for a long time. What explains its charm?

MAZZOLA: I don’t know if “charm” is really the correct word for the question, because “charm” suggests that you can just sit and enjoy it in a very pleasant way. Every operatic event is to be enjoyed, of course, but there is tremendous energy in Ernani. A dark power, if you will — the violence of the jealousy, of the misunderstanding, of the price and cost of honor.

ANDRE: For Verdi, Ernani is kind of a new beginning. He had gotten settled with four operas at La Scala, the best-known northern Italian theater, first with Oberto (1839), which was a success. Then Un giorno di regno (1840), a comedy that flopped. Then you get Nabucco (1842), and I Lombardi alla prima crociata (1843), which were both popular, and then offers start coming in. The La Fenice theater in Venice comes calling and Verdi is like, “Sure, I’m interested. Sounds great. Something for a theater outside Milan.”

MAZZOLA: Ernani was an immediate, huge success, and it remained popular throughout the 19th century. It was still performed at the beginning of the 20th century, when it became something of a rarity — it didn’t disappear, but it was never a big hit again. And what is strange is that, probably until Il trovatore (1853) or La traviata (1853) or even Rigoletto (1851), Ernani was actually the most — in Italian we say un cavallo i vertalia libertalia.

ANDRE: A war horse!

MAZZOLA: Yes. And that’s why our audience should come to experience Ernani. It’s wonderful to explore a great opera by the young Verdi at his most energized, impassioned, and sincere.

ANDRE: Ernani is Verdi at an international moment. Along with Nabucco it was the first to be heard in London (in 1845) and it was Verdi’s first opera to be translated into English. This is also his first opera closer to the present — it’s set in the 16th century, whereas the others were from biblical times or the Middle Ages.

MAZZOLA: Also Verdi’s use of the work of Victor Hugo was terribly modern. He was one of the most controversial writers of the time. It was really an act of courage to portray onstage the weakness of a king or the aristocracy when confronted by a bandit. For us, when we go on Netflix, we see villains everywhere. It’s normal. But for the people of the time, this was revolutionary.

ANDRE: Absolutely. Because remember, this is 1844, so you have the whole unification movement, Il risorgimento, happening in Italy. To have anything about political unrest with a king not being the main character, but a person outside the law, that’s very modern. This is his first Hugo source, and the next would be Rigoletto, also for La Fenice in Venice. The point is that this is a big moment for Verdi, when he’s first getting a wide reputation. It’s a real milestone. To take this into Venice is a big deal.

MAZZOLA: Absolutely.

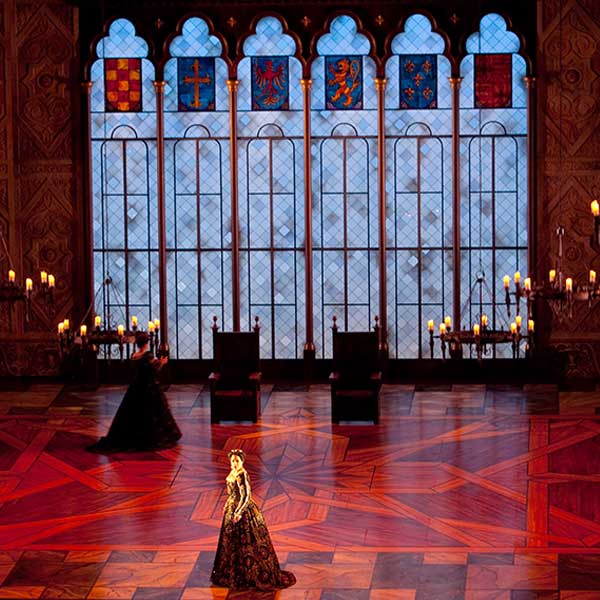

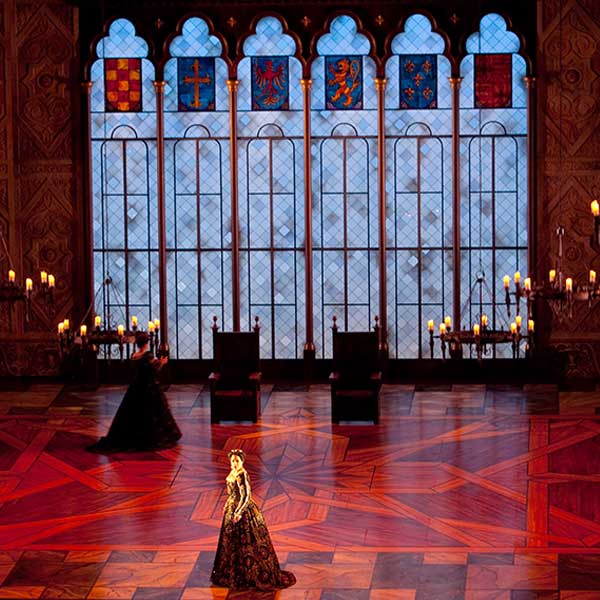

From left to right: Quinn Kelsey (Carlo), Tamara Wilson (Elvira), and Christian Van Horn (Silva) in Lyric's 2022/23 production of Ernani.

I understand Verdi really had a hand in all aspects of the premiere of Ernani, including working closely with librettist Francesco Maria Piave.

ANDRE: Piave eventually becomes his most frequent collaborator, and this sort of starts that important relationship. There’s a definite fondness, and when Piave died, Verdi helped his widow and family. I get the sense there’s a deep friendship there, but in the letters Verdi wrote to Piave, you can see that Verdi can be tough. He’s always pressing, saying things like “Come on, do something better. I’m not even a librettist and I can do better than that.” There are all these versification rules that went with la solita forma [the conventions of the scene structure for arias, duets, and other elements during the first half of the 19th century]. And Verdi’s always wanting fewer words. Here is a quotation from an 1843 letter: “Let’s have as few words as possible…Remember that brevity is never a fault…. I never try to shackle the genius of my poets…but I do insist on brevity because that’s what the public wants.”

MAZZOLA: This is one of the most important points about Ernani. Verdi wanted an extremely compact opera. He didn’t want to write a huge, sprawling work, a Don Carlos or a Boccanegra. That insistence with Piave was because he was convinced that brevity is the key to success. Ernani is written in four acts but it’s actually about the length of a normal two act opera. It was the same for Donizetti, with Poliuto [premiered at the Paris Opera as Les Martyrs in 1840]. It’s absolutely concise, and I would say that this is a characteristic of the composers of the 1830s and 1840s — trying to go into the drama in a very fast, impactful way.

ANDRE: Wow — people don’t usually mention Poliuto! Yet you make an excellent point that Donizetti was an important force for reworking le solite forme to heighten the theatrical energy. People want to make Verdi the maverick, and he was very knowledgeable. But he went to everything; he was listening and watching opera all over Italy and Paris. And he was a great synthesizer, especially in his works — like Ernani — from the 1840s. He got many ideas from other composers—particularly Donizetti.

MAZZOLA: Brevity was an important ingredient in the big pot of what we call bel canto style.

ANDRE: Ernani lets us see Verdi, just as you’re saying, really embracing the bel canto, which I frequently refer to as the primo ottocento [roughly the first half of the 19th century, when Bellini, Donizetti, Rossini, Verdi, and numerous minor composers thrived].

MAZZOLA: Yes. There is an emphasis on climactic cabalettas: a very fast, athletic, high-gear style at the end of the scenes. Bel canto in Verdi’s hands — he embraces it. It was not a language; it was the language. Then slowly, starting with the trilogy of Rigoletto, Il trovatore, and La traviata, he started breaking away from the constraints. His extraordinary creativity couldn’t be contained within the rules of bel canto, so he broke and eventually abandoned them. This is a musical evolution you cannot compare with anyone else’s. Among all composers, maybe with the exception of Wagner, Verdi is the one who made the longest journey, reinventing himself, rebuilding himself. From the first Donizetti to the last Donizetti is not a big trip. But from Oberto to Otello (1887), we have a half century of completely new compositional and dramaturgical inventions.

ANDRE: You’re absolutely right. Ernani is Verdi becoming Verdi. In this opera we see him pointing us towards the well-known chestnuts, particularly that middle trilogy. Abramo Basevi, a critic of that time, uses a helpful term — tinta — to describe the specific colorings in Verdi’s operas. Verdi’s works have different vocal and orchestral moods, sounds, a different tinta to express their different personalities. A great example is Simon Boccanegra, one of his darkest operas. Though you get all those male voices, Ernani isn’t as dark as Boccanegra; instead, it has a heroic sound, with all the brass and the military connections. Yet Ernani is still dark in terms of the male voices and this focus on what is defined as the ‘men’s business’ of honor and war and politics.

Tamara Wilson (Elvira) and Russell Thomas (Ernani) in Lyric's 2022/23 production of Ernani.

MAZZOLA: Inside all the virtuosic, even heroic vocal output of this opera, there is an island of that darkness. It’s the beginning of the third act, at the tomb of Charlemagne, when the characters go into the subterranean vaults.

ANDRE: I’ve listened to the music recently, and I agree — the feel is very different there. You’re in these vaults, and then you’ve got the conspirators, and it’s almost like looking toward Act IV of Don Carlos (in the five act version) where you have King Philip II in the vault. It’s dark, he’s alone, and it’s such a personal, intimate moment.

MAZZOLA: Exactly. And in Ernani it is in some ways the quintessential Romantic scene. The Romantic imagination lives underground, with maybe a ray of sun entering through a small window. The prelude here is scored for two clarinets and two bassoons in the lower register, and in just a few bars we have the Verdi of the future. It’s exactly the same in the last 20 minutes of Luisa Miller, the opera that started Lyric’s exploration of the early work.

ANDRE: Agreed. Luisa Miller is already transitional, I would say, between the early Verdi style and the mature central period.

MAZZOLA: I’m used to living in that Verdi time machine. In Luisa Miller, we have that brilliant, somewhat leggiero Verdi, through the beginning and throughout the middle of the opera. And suddenly the opera goes down into the subterranean depths of the human soul.

ANDRE: That’s fascinating. I love all of opera, and I can listen to recordings of early Verdi, but when you hear them live, that brings them to the present. I’m so glad you — somebody who sort of lives and breathes them — are bringing them to Chicago.

MAZZOLA: I’ve become used to finding in almost every early Verdi opera, places where you think this is an Otello or an Aida moment. It’s something that rarely happens in Bellini or Donizetti. They are much more consistent. I’m not a musicologist, but I can say that this is my experience when rehearsing and performing. When I’m conducting Ernani, I’m thinking, “This is not 1844!”

ANDRE: I love that.

MAZZOLA: And that’s my invitation to our audience. To discover how different that Act III prelude sounds, to really savor the change of atmosphere, which is in some ways very modern. I have a feeling that’s partly why 19th century audiences went crazy for this opera. And it’s hopefully what will make our audiences in 2022 go crazy for Ernani as well.

September 09 - October 01, 2022

Ernani

Ernani

The 2022/23 Season opens with a thrilling continuation of Lyric's acclaimed early Verdi series. This "love quadrangle" inspires grand-scale arias and ensembles, bursting with the unique energy and drive that were Verdi's own. Music Director Enrique Mazzola leads a quartet of world-renowned Verdians in Lyric's sumptuously beautiful production that is designed to bring you an exhilarating operatic experience.