February 21, 2025

True Colors: Women and la vie bohème

A selection of 19th-century works from the collection of the Art Institute illuminates Puccini’s conception of bohemian life — and reveals the unsung contexts of the lives of Mimì and Musetta.

Mère Grégoire by Gustave Courbet, 1855

Last spring, as we strolled through the Art Institute of Chicago's 19th-century collection, former Lyric General Director Anthony Freud noted the preponderance of paintings of women — many of them legendarily gorgeous works. I pointed out that these were not always depictions of innocents or grande dames, but rather were often coded images of prostitution, one of the few paths of survival (besides marriage and motherhood) for single, working-class females of the time. And at that moment we had a mutual revelation about how paintings by Toulouse-Lautrec, Courbet, and even Renoir, among others, could illuminate much of the backstory of La Bohème and its compelling characters.

Puccini himself, and his audience, would have understood the unspoken tensions inherent in the works of French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters held at the Art Institute — and indeed it's fair to say that the social observations in the paintings are echoed in his operatic renderings of Mimì and Musetta. In Bohemian life, there is abundant beauty, but plenty of darkness as well.

The concept of Bohemianism, which originally referred to transient peoples, especially the Romani, had morphed in the 19th century to define a non-conformist lifestyle opposed to bourgeois conventions of respectability. Synonymous with art culture, Bohemianism was not only an urban phenomenon but, as the French writer Henry Murger specified in his introduction to Scènes de la vie bohème, Puccini's source material, it "only exists and is only possible in Paris."

Puccini's fourth and most beloved opera, La Bohème draws not only on Murger's tales of the alternative lifestyle of artists, writers, and musicians in the Latin Quarter of Paris, but also on his own experience as an impoverished composer in Milan, when he too lacked the means to pay for food, heat, and rent. His first actual visit to Paris, however, was a business trip in the mid-1890s, around the time he was composing the opera, which premiered in 1896 in Turin. We know little about that visit and whether or not he ventured up to the Butte (hill) of Montmartre, the undisputed mecca of bohemianism, whose lower rents and romanticized promises of sex and debauchery continue to attract artists and tourists today.

The Laundress by Auguste Renoir, 1877-79

Puccini's sentimental love tragedy takes place in studios and cafés, prominent symbols of Montmartre's subculture; seen on the backdrop, a hint of the unfinished Tour Eiffel specifies this production's moment as the late 1880s. Here we are introduced to the painter Marcello, poet Rodolfo, and (later) musician Schaunard, true bohemians convinced of their talents and future while living in obscurity and poverty. More to our point, we meet Musetta and Mimì, who represent the reality of single women in an increasingly populated, expensive, and patriarchal society where prostitution was not only accepted but regularized in the service of men. Puccini had already written an opera about a famous prostitute, Manon Lescaut, the glittering 18th century courtesan, who metaphorically preys upon men wealthy enough to provide her with a life of material luxury. La Bohème presents two members of the less exalted echelon of prostitution: Mimì, inherently innocent of greed and vengeance, whose incentive is survival, and Musetta, a spirited singer, escort, and call girl.

By the second half of the 1890s, when Puccini's opera was produced, prostitution was both an entertainment and a vice, whose practitioners were identified as filles publiques, pierreuses (from the cobblestones streets they walked), filles de joie, and belles de nuit (loosely translated to public women, streetwalkers, joy girls, and beauties of the night), among other pejorative monikers. Apart from the Courtesan, an expensive escort who benefitted from extremely wealthy suitors, and whose fashions and styles were emulated by respectable bourgeois wives, the majority of prostitutes came from the country and needed money not only to keep themselves alive but frequently to support other family members. At the same time, prostitutes were not considered professionals (what one would call sex workers today) but social deviants, and thus a threat to the nuclear family and subject to rules set down by the very men who profited from their availability. Thus began the two-tiered system of "soumises" (literally, subjugated by the police) and "insoumises" (unregulated). The former refers to women who worked for a maison de tolérance, or brothel, and were forced to follow house rules in terms of clientele, wages, and living conditions; the latter refers to those like Mimì and Musetta, free from those restrictions but, as independents, more vulnerable to the vagaries of fortune.

Both sides of the prostitution coin became popular subjects for artists by mid-century. Mère Grégoire, painted by the undisputed leader of Realism, Gustave Courbet, was inspired by a popular song written in the 1820s by French lyricist Pierre-Jean Béranger about the proprietor of a house of prostitution known as Madame Grégoire. Courbet's "Mother Gregory" (1855) is a demurely dressed and ample middle-aged woman depicted in the midst of a transaction, with coins scattered on a marble-topped counter, a ledger beneath her right hand, and a small bell used to summon her female employees. She appears to be accepting payment while offering a flower, the symbol of love, to a paying customer — all of which, for those familiar with the song, could easily be decoded and aligned with Béranger's ribald lyrics.

Courbet's hidden message alludes to Madame Grégoire's filles soumises, and represents a sex trade that had specific rules that unregulated prostitutes did not follow. In contrast to brothel workers, covert prostitutes could be any working-class women not protected by marriage or family — including barmaids, laundresses, flower sellers, artist's models, entertainers, or, like Mimì, underpaid needleworkers — who were forced into prostitution or cohabitation with a man in the hope of finding steadier circumstances.

The Impressionists, whose compositions of modern life frequently signaled flirtatiousness and sociability among the sexes, did not shy away from imaging prostitution in paintings seemingly observed from life rather than modeled in a studio. (This notion is examined in depth in Hollis Clayson's brilliant 2003 work, Painted Love.) Degas, for example, painted young laundresses, milliners, and pubescent dancers from the Parisian corps de ballet who often supplemented their meager earnings with sex work. Although now seen as part of the joie de vivre characterizing Impressionism, numerous works by Degas and other painters of modern life often concealed a sinister undertone, touching upon controversial 19th century aspects of women's work outside the home. Indeed the free-ranging fille insoumise was a central theme in bourgeois culture, as shown more explicitly in the 1899 scene In the Wings by Degas' close friend, the graphic artist and painter Jean-Louis Forain.

In the Wings by Jean-Louis Forain, 1889

As shown above, backstage at the opera, two elegantly dressed men confront a ballerina: one directly addresses her while another looms just behind, so close that his black top hat overlaps with her orange headdress. For contemporary viewers their intentions would be clear. They represent wealthy fellows of the Jockey Club, whose membership included backstage privileges that allowed special access to the dancers. Although the ballerina's stoic demeanor suggests an indifference to their advances, Forain's artful fiction belies the reality of sexually exploited young ballet dancers, whose career and finances depended on finding favor among male donors.

In Impressionist paintings from the 1860s and 1870s, the prostitute's stark plight and social oppression was often prettified by art. Auguste Renoir's 1877-79 The Laundress, shows his favorite model, Nina, without any reference to the backbreaking labor involved in her profession. Instead, Renoir adheres to the stereotypical characteristics of laundresses from the male viewpoint: promiscuous and available. He paints her artfully disheveled, rosy-cheeked, standing with hands on her hips, with one sleeve slipping seductively off her shoulder.

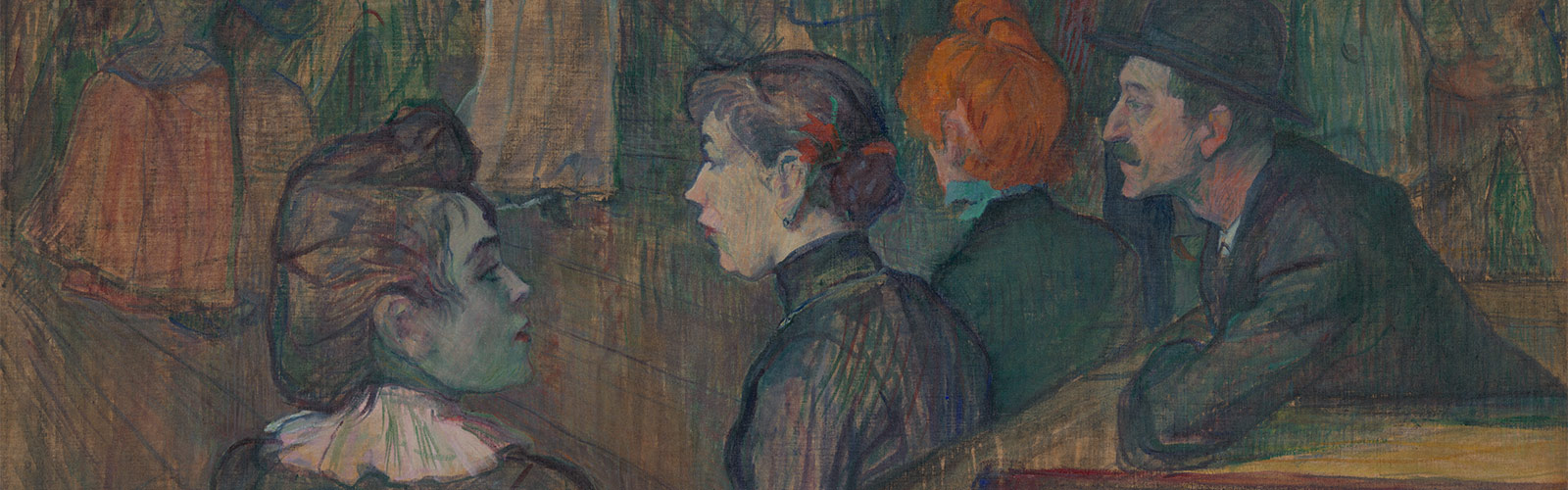

It was not until the end of the century that artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec began to depict women, either on the street or in the brothel, more straightforwardly in large-format paintings. As a provincial aristocrat who embraced the counterculture of bohemian nightlife, Lautrec became the chronicler of the café concerts and cabarets of the Butte, where dancers and singers, also insoumises, found their prey. As in the café scenes of La Bohème, in Moulin de la Galette (shown at top) Lautrec presents an atmosphere of hedonism where a mixture of drink, crowds, dancing, and even the presence of gendarmes contribute to the promiscuity associated with nightlife and prostitution. A wooden barrier bisects the women seated in expectation of an invitation that will lead them to the dance floor; they are under the surveillance of the bony man seated behind them, described by the scholar Richard Thomson as "Alphonse, the enforcer, or pimp."

In his later and most celebrated nightclub scene shown below, At the Moulin Rouge, expensively fashioned female dancers and singers (including Jane Avril, with her signature red hair and fur-trimmed dress, seen from behind) share a table with well-heeled gentlemen. Like Puccini's Musetta, who ascends from call girl and café singer through her relationship with the Count, Avril is a former can-can dancer whose marriage to artist-designer Maurice Biais lifts her out of her envisaged trajectory as a professional prostitute. In this crowded and chaotic scene of mirth and vice, Lautrec, the noticeably short man at center, just above Avril's head, presents himself strolling with his cousin Gabriel de Tapies, as a detached observer to the debauchery inherent in Montmartre nightlife.

At the Moulin Rouge by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1892/95

When I think of Musetta's role as ostentatious performer on and off the stage, I can almost imagine her as the subject of another figure of clandestine prostitution painted by Lautrec's close artist friend, Louis Anquetin. In his 1888 work, A Woman at the Élysée Montmartre (shown below), an unidentified woman is shown strolling under the electric lights of an outdoor beer garden behind a popular dance hall. Exaggeratedly made-up with rice powder, she is inappropriately attired, her outrageously over-decorated hat completely incompatible with the nighttime atmosphere. Her unbuttoned peplum jacket is flung open to reveal a colorful, unexpected lining, as well as the plunging neckline of her red and white printed dress. The fact that she is alone with a frothy beer on the table suggests that she is a performer, and possibly a woman on the prowl for clients. Reinforcing this second explanation are the slender sylph-like women slipping between the trees in the background, their predatory nature even more pronounced. These are truly ladies of the night in search of their next protector/victim, representing as much the prostitute as the femme fatale that would be a highly popular theme for symbolist art and literature at the turn of the century.

Mimì and Musetta, too, are products of the male imagination, and the numerous ambiguities in the paintings adhere to the sopranos as well. Are they really victims? Clearly, they did not choose their lifestyle, but did they not benefit from the advantages it provided?

Although we are not given any information on Mimì's past, we know she is a good girl whose youth, beauty, and availability help her to subsidize her meager income as a seamstress. In fact, the complications of her life stem not from her work either as a needleworker or prostitute, but from the circumstances of poverty and, of course, her medical condition. It is consumption that defeats her rather than her membership in the popular classes. On the other hand, she is not without agency. In financial distress, she seeks recourse in males, like Rodolfo, leaving us to speculate whether her chance encounter over a blown out candle and dropped keys, causing Rodolfo to touch her cold, little hand and thus ignite the romance that temporarily saves her, is a true coincidence or part of a calculated flirtation.

No matter how poor, the male bohemian was never as destitute and vulnerable as the single female. Males could hang out in public, alone or with friends, and not be suspected by the police for their overt sexuality; and they would always have male fraternity to fall back on, which Puccini makes clear in the raucous antics of the artists of the ateliers and cafés. Never completely alone, a male bohemian could be single and poor but never without resources, and never as destitute as those like Mimì.

The triumph of La Bohème resides in how Puccini detours from the visual detachment and subtlety so important to the artists discussed here (Forain excepted). Though Rodolfo becomes Mimì's enabler, encouraging her mission to seduce a wealthy benefactor, he is also genuinely smitten. Their story, set against the dream of artistic freedom, is also a realistic tale of the inequalities between men over women — inequalities present in the worlds of painting, literature, and opera alike; love conquers, for a time, but is defeated by the rules of society, which work against them. Indeed, this unforgettable work of art is ultimately inspired by the darker side of bohemian culture — a tragedy rather than a rhapsody.

A Woman at the Élysée Montmartre by Louis Anquetin, 1888

Gloria Groom is the Chair and Winton Green Curator for Painting and Sculpture of Europe at the Art Institute of Chicago. Her current exhibition and catalogue, Gustave Caillebotte: Painting his World, in collaboration with the Musée d'Orsay, Paris, and the Getty Museum, opens at the Art Institute in June.