October 24, 2019

The journey of DEAD MAN WALKING

By Jake Heggie

When Terrence McNally and I first met in 1996 to discuss a possible opera collaboration, it was a comedy that the producer had in mind. Something light and celebratory for the millennium. Being virtually unknown as a composer, with this incredible opportunity placed before me, I was hardly in a position to disagree with Lotfi Mansouri, San Francisco Opera’s general director. Terrence, however, was. And he did – he couldn’t have been less interested in such a project.

Jake Heggie

With Terrence’s passion for opera and my devotion to composing for the operatic voice, Lotfi believed that this collaboration must happen. Removing the mandate of comedy, he asked us to find a story that would inspire both of us. In mid-1997 in San Francisco, Terrence and I sat down to lunch and he brought out a list of ten ideas, only one of which he really wanted to do. He wouldn’t tell me which it was. He started reading the list. Dead Man Walking.

The hair on the back of my neck stood up and I immediately started to hear music. This was the right story. He continued reading, but to this day, I can’t remember any other idea because I was already figuring out how Dead Man Walking would sound. What kind of architecture would the music have? What kinds of musical motifs? The range of characters and their transformations was incredible. There would be room for large ensembles and great possibilities to build emotional tension, to find transcendence in musical terms. Fortunately, that was the idea Terrence was most enthusiastic about, too.

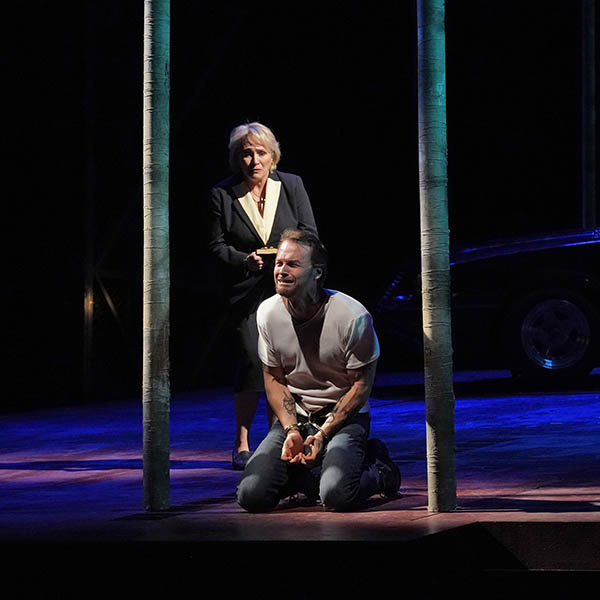

Patricia Racette as Sister Helen

Why was the story so compelling? Sister Helen Prejean, a Louisiana nun, becomes the spiritual advisor to a convicted murderer on death row and accompanies him to his execution. She experiences a journey most of us can’t imagine and witnesses a level of grief that even she hadn’t imagined. Parents. Children. Families. Torn apart. Amidst all the grief, tragedy, loss, and anger, it’s love that transcends, unites, and redeems. Very operatic stuff.

We wanted our opera to be a contemporary American drama. Dead Man Walking is a story of our time, but also timeless – a distinctly American story, but with universal resonance.

This drama makes sense for people to sing and is large enough to fill an opera house, yet it’s incredibly intimate. It takes us deep into the most difficult struggles we can experience, and to places that only intensify with music. The more we talked about it, the more it seemed like an opera just waiting for the music.

Much as we admired and respected Sister Helen and her nonfiction book, Dead Man Walking, the opera wouldn’t be a documentary or a biography. It would also not be a “soapbox” opera pushing a political agenda. We didn’t want to recreate Tim Robbins’s brilliant movie, either. We would go from the book, telling the story honestly without preaching, while letting people make up their own minds.

Supportive and enthusiastic from the start, Sister Helen allowed us to do whatever was needed for her story to work onstage, with only one mandate: it had to remain a story of redemption. Right before the announcement of the project, Sister Helen called me and said, in a thick Louisiana accent, “When they called and told me that San Francisco wanted my permission to make an opera out of Dead Man Walking, I said, ‘Well of COURSE we’re gonna make an opera out of Dead Man Walking!’ But, Jake, I don’t know boo-scat about opera, so you’re gonna have to educate me.”

Why is Sister Helen such an operatic character? Against the enormous background of the prison system, death row, and a man convicted of a monstrous crime, there is this one small woman and her faith: her belief in the individual dignity of every person on earth. She travels this path as a kind of “everyman,” and it’s easy for us to go along: from the security of working with children in the projects to meeting a convicted killer, then his family, then the families of the murder victims, to an execution chamber, all propelling her to a place of spiritual crisis and ultimate resolution. At first, she’s like one of your gal pals, with great humor and zest for life – neither we nor she are aware of the bravery and power inside her when she’s tested. But I think it puts all of us to the test: How much could I take? How far could I go? What are my convictions?

It’s this that makes these characters operatic, for they’re all regular folks thrown into a tornado, being tested, strained, and pushed to the edge. The story puts a human face on capital punishment. It’s no longer a comfortable question one can consider while watching television or reading the paper. Real lives are at stake at every turn in this story.

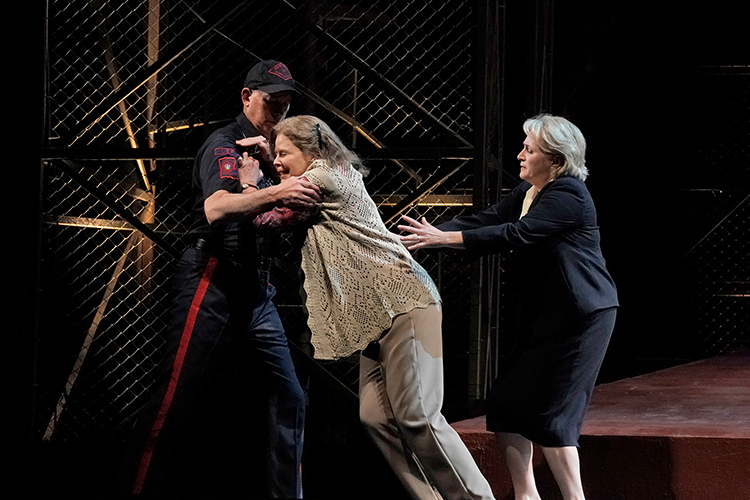

Susan Graham as Mrs. De Rocher and Patricia Racette as Sister Helen

Terrence told me that he intended to write a play, creating language and situations that would inspire music. He recognized that an opera is about the music, and that he’d do whatever he could to serve that. If the music took me in a certain direction, I should follow it. If his words didn’t work for me, I could add my own, checking with him later. It’s the most generous, gratifying collaboration a composer could hope for. Another goal was to explore a medium that was neither traditional theater nor traditional opera, but a music drama, an opera musical, opera theater, or perhaps finally, American opera theater.

My compositional voice is based primarily on direct emotional portraits of characters. I wanted clear melodic and rhythmic motifs to propel a constantly moving tide of emotion with lyricism, without alienating the characters or the audience. The piece’s architecture was clear, too: a building of layers throughout Act One – a long crescendo to the point where Sister Helen faints, overwhelmed by the emotional intensity and the demands made on her. Act Two, a gradual stripping away of layers to reveal the essence of what is at stake: life and love. Since the San Francisco Opera premiere in 2000, the opera has received more than 300 performances by 70 international companies on five continents. Director Leonard Foglia’s production, first seen in 2002, has traveled to more than a dozen U.S. opera houses as well as Madrid’s Teatro Real. New casts and productions continue to bring different perspectives to the opera. But it’s Sister Helen’s compelling journey that continues to capture the imagination; our opera, hopefully, continues to take people right along with her.