November 13, 2021

Magical journey: Andrea Puente Catán welcomes Florencia en el Amazonas to Lyric

When Daniel Catán’s music is performed in any important venue, it’s likely that Andrea Puente Catán will be present. As her late husband’s most passionate and persuasive advocate, she’s the best possible guide to Catán’s musically ravishing, dramatically riveting Florencia en el Amazonas, the first Spanish-language opera Lyric Opera of Chicago has ever presented in its mainstage season.

Originally a professional harpist, Puente Catán is former cultural ambassador of California’s U.S.-Mexico Chamber of Commerce, and currently holds the position of director of major gifts and Hispanic initiatives at San Diego Opera. Nonetheless, her greatest mission is to encourage interest in Catán’s music internationally. When reached via Zoom, she was deep into planning a full-length film of Catán’s opera Rappaccini’s Daughter, a bi-national project to be produced in San Diego and Mexico.

“I think Daniel and I still have a continuing partnership,” says Puente Catán. “When you get married, you say ‘in life and death.’ This is a clear example of going beyond death. I’m Daniel’s biggest supporter in the way I dedicate my life to promoting his works. I share them with so many people! It’s important that his music continues to be played, and that people’s hearts are touched by it.”

When San Diego Opera presented Rappaccini’s Daughter in 1993, Daniel Catán’s music was comparatively little known in America; the piece was the first opera by a Mexican composer to be presented by a major American company. Puente Catán recalls that after seeing the production, David Gockley, general director of Houston Grand Opera at the time, commissioned Catán to write a new opera. Initially, Gockley hoped to launch a producing partnership with Colombia and Mexico, but that never happened; instead, Florencia en el Amazonas became a three-company commission, with Houston presenting the premiere in 1996, followed by the other partners—first LA Opera, then Seattle Opera. Florencia was finally produced in Mexico earlier this year to celebrate the work’s 25th anniversary.

The libretto was the result of a close collaboration between Catán and prominent screenwriter Marcela Fuentes-Berain. The two developed the characters together, and given Catán’s own passionate devotion to the printed word, it was fortunate that Fuentes-Berain’s writing was exquisitely elegant. Among Catán’s many literary friends was another celebrated writer, the late Álvaro Mutis, who had been the best friend of the legendary Gabriel García Márquez. “Álvaro loved boats and rivers,” Puente Catán recalls, “and he was actually a big influence on the libretto.”

The overriding inspiration for Florencia was García Márquez, whose works are pervaded by magical realism. When asked for her perspective on that concept, Puente Catán explains that “it’s when fantastical things happen in people’s lives. For Latin Americans, it’s like those magical moments are integrated into the way we live.” An example from her own life reveals exactly what Puente Catán means: “My aunt died, and three days after, I suddenly found her little box with threads and needles and pins on the stairs of my house—yes, this actually happened! Instead of me saying, ‘Maybe this dropped from a bag,’ I said, ‘Oh, my niña came to visit and left me this box just to remind me that she’s still around.’ I’m a Latin American person, and I grew up with the notion of magical realism. There’s a fine line between the real and the fantastic. For Latin American people, fantastical things are as concrete as reality! If you asked me today, ‘Do you really believe that your aunt came to say hello?’, I’d say, ‘Yes. She was leaving me her little box to remember her.’”

Florencia isn’t based on a work of García Márquez, but Catán’s piece is steeped in the writer’s oeuvre. “Daniel talked about García Márquez’s relationship with love in his books . . . the impossibility of love; even though there are a lot of characters who are in love or want to be loved, in the end something happens and the love doesn’t continue. García Márquez’s writing fascinated Daniel with its marriage between fantastical moments and concreteness. His use of the Spanish language is just extraordinary. I think Daniel was very drawn to García Márquez’s sense of narrative. Also, in Florencia, the whole notion of being on a boat searching for one’s lost love bears a resemblance to García Márquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera. I invite everyone to read that book after they see Florencia, so they can understand exactly what the book and the opera have in common.”

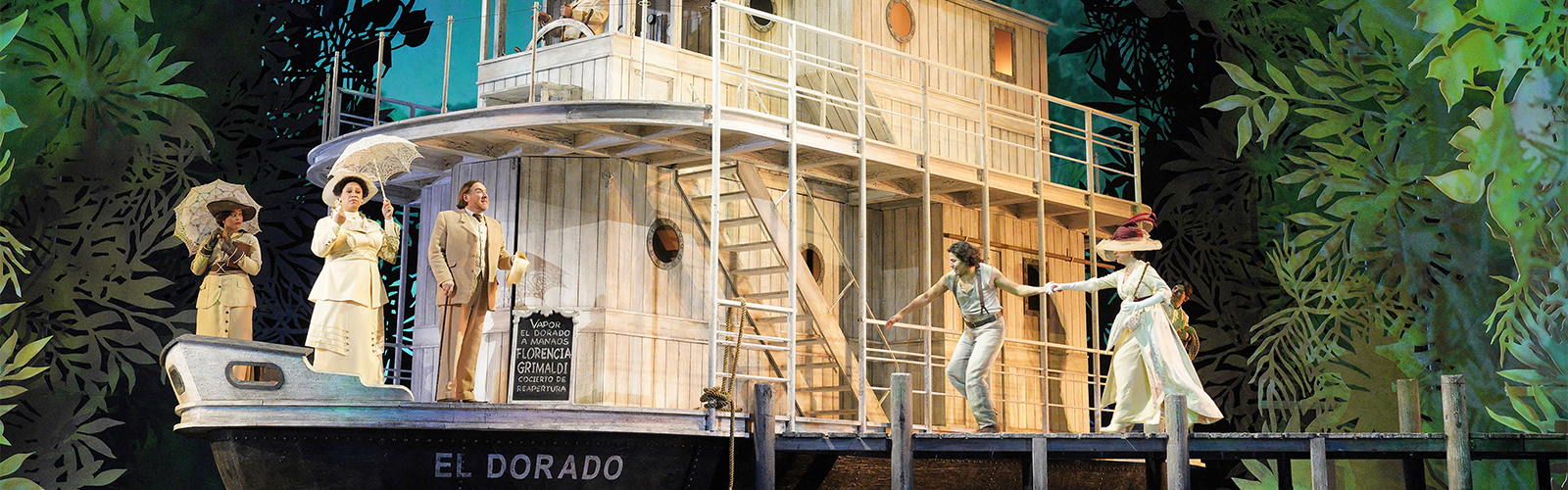

Central to the libretto is the boat on which all the action takes place. Its special significance is noted by Puente Catán: “The boat is called the El Dorado, a name that has many connotations for Latin Americans. You can think of the Spanish searching for gold, but more than that, the name makes you think of sunshine in your life. Daniel’s mother called him not ‘my son’ but ‘my sun.’ We hear El Dorado and think of something that is gold-like, related not to wealth, but to luminosity.”

The opera’s plot integrates more straightforward characters — the younger and older couples, the captain, and Florencia — with a particularly enigmatic figure: the omnipresent Riolobo. Puente Catán describes him as “a creature of magical realism. On the surface he’s just an ordinary man who works on the boat, which he knows inside out, but he’s also like the wise man of the jungle. When the boat is going into the storm, he has an aria in which he becomes a flying creature. He’s like a shaman, in a way — a shaman of love and of the river. He’s as real and concrete as you and me, but he can transform himself and speak the language of nature.”

The Arcadio-Rosalba character relationship involves much intense emotional discussion of the negative elements of falling in love. Puente Catán considers it “very autobiographical for Daniel — as were all of his works, in a way. They’re his love life in different stages. In Florencia, the music is telling us that Arcadio and Rosalba actually want to be together. We hear them saying, ‘Goodbye, I don’t want to be with you’ while the music is saying, ‘I love you.’ That’s an ‘A-ha!’ moment.”

The drama of Florencia also is intriguing in its mysterious ending. “The Latin American literary tradition includes several books that end like this — with a question mark,” says Puente Catán. This impression is enforced in the score’s final moments; the music doesn’t end with the root (the strongest note in any chord), but instead emphasizes the fifth note of the scale — the dominant — which lends an uncentered, unsettled feeling to the harmony. “That’s what makes it inconclusive, and I feel it when I hear the final timpani. Daniel wanted it this way so that everyone in the audience could create their own ending. For me, it’s all about Florencia’s energy becoming part of nature.”

Florencia’s sound world connects with Catán’s trip down the Amazon at the time he was composing the opera. Puente Catán recalls that he retained a vivid memory of “the early hours of the day, with the sun coming out and all those birds and insects waking up. I think you can hear that a lot in Florencia in the flutes, clarinets, and oboes. There’s also an interlude in which the sun comes up and you hear the chirpy sounds of birds.”

Catán’s operas have caused critics to cite certain musical influences (one Florencia review mentioned everyone from Puccini and Strauss to Ravel, Debussy, Stravinsky, and John Williams). Puente Catán accepts the fact that “some critics find it impossible to say a composer has his own style. As the years pass and Daniel’s works continue to be played, everyone knows now that when you hear the first five chords of Florencia, this is Daniel Catán! Yes, he was influenced by many composers—Strauss, Debussy, Berg, Stravinsky—but composers aren’t born from nothing. They all have to have some kind of influence. It’s interesting in Daniel’s case: he has clear German and French influences and then Latin American as well. You put these elements together and this is what you get!”

Florencia’s orchestral colors make a mesmerizing impact. Puente Catán especially loves the final notes of the opera, scored for violin, piano, harp, and timpani. “Daniel’s combination of timbres is very particular. His use of harp, steel drum, and marimba, which he then incorporates into the fabric of the strings, woodwinds, and brass, is amazing.” The Florencia score marvelously matches strikingly distinctive sounds with dramatically astute use of specific rhythms. “In the storm music, for example, there’s a combination of rhythms — groups of nine notes with a lot of movement in the orchestra because the boat is sinking. Then, we have this ‘chak-achak-a-chak-a:’ the boat engines! Suddenly, the music moves into a ¾ tempo and slows down, and it’s like the sun interrupts the storm as Florencia, Rosalba, and Paula sing about their loved ones. It’s a return to life, with the sound now like a cushion, a wave of strings.”

Lyric is presenting a production of Florencia that Puente Catán considers eminently worthy of the piece. “[Director] Francesca Zambello put together an incredible team. The boat is quite large and lifelike, but within it there are some wonderfully intimate moments. When Rosalba and Arcadio are talking about love, they’re in a part of the boat that is almost like a little box within a much larger structure.” Puente Catán also greatly admires the lighting, and the production’s treatment of the Amazon itself. She’s grateful that “Francesca has what I would call an ‘aesthetic respect’ for the opera.”

Andrea Puente Catán hopes Lyric’s performances of Florencia en el Amazonas will help to fulfill Daniel Catán’s passionate wish to “give voice to Hispanic artists in America. This was so important to Daniel. It can encompass anything, whether it be art, dance, literature, or music.” She hopes, too, that Florencia will leave the audience with a special feeling not only for the opera itself, “but also with the belief that love is possible.”

Roger Pines, former dramaturg of Lyric Opera of Chicago, writes regularly for major opera-related publications internationally and has been a panelist annually on the Metropolitan Opera broadcasts’ Opera Quiz since 2006. He currently teaches an opera repertoire course at Northwestern University’s Bienen School of Music.

November 13 – 28, 2021

Florencia en el Amazonas

Florencia en el Amazonas

Lyric’s first Spanish-language work to be presented as part of the mainstage opera season, this story about a glamorous diva on a life-changing adventure on the Amazon is suffused by the entrancing allure of magical realism. Florencia Grimaldi, a renowned diva, is engaged to perform at the opera house of Manaus, Brazil. Traveling there by boat, she’s consumed by longing for her long-lost lover, who she hopes will be awaiting her. Florencia and her fellow passengers are all intensely memorable characters, and they’re illuminated by the magnificent, sumptuous romantic music created by a true musical genius — Mexico’s finest opera composer, Daniel Catán.