April 17, 2019

Modern Match - Il trovatore

The hero of Il trovatore, Manrico, is introduced in the opera as an adult, but the mystery of his character can only be unlocked when we understand what occurred during his infancy. In this and other ways, he’s similar to another boy we know well: Harry Potter.

Manrico was raised never knowing his true family, including Count di Luna, who turns out to be his brother. As a result, the two men are unable to recognize each other in adulthood, yet Manrico seems to understand implicitly that their destinies are linked. In his duel with di Luna, he couldn’t bring himself to harm him when given the chance.

J.K Rowling's Harry Potter (Daniel Radcliffe), with Hermione Granger (Emma Watson) and Ron Weasley (Rupert Grint)

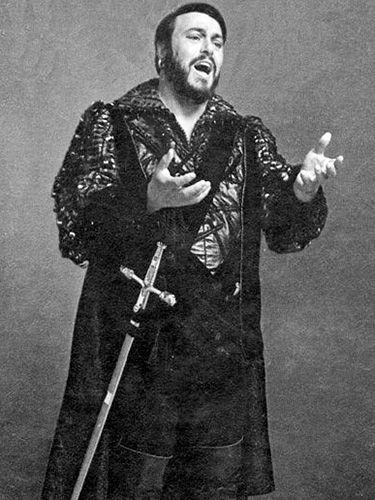

Luciano Pavarotti as Verdi's Manrico

Harry, too, was raised as an orphan, but discovers throughout the book series that his destiny is inextricably linked with Voldemort’s. Though the two are not true brothers, J.K. Rowling kins the two thematically. For example, Harry and Voldemort use magic wands made out of the same material, called “brother wands,” which recognize and refuse to do the other harm during an important duel. Harry and Voldemort share other curious similarities – such as a hereditary ability to speak to snakes – that elevate their relationship to being almost fraternal. In both the opera and the Potter novels, the brother-figure is one of rival or foil, a reflection of what the other could be had circumstances been different. In their similarities, their differences stand out in stark contrast and give insight into the characters.

But brotherhood isn’t the only family role that takes on twisted significance in both stories. In each case, a mother rescues her young son and makes it possible for that son to grow into the hero he was always meant to be. In Harry Potter, it’s Harry’s mother Lily who, by sacrificing herself, casts the spell that saves the infant Harry from Voldemort. Manrico’s life is saved by Azucena, who unwittingly sacrifices her own child and consequently becomes his adopted mother. As a result, Manrico is fiercely loyal to her, just as Harry is loyal to his own surrogate mother-figures, Mrs. Weasley and Professor McGonagall.

Though both stories make use of these tentative family relationships, they end very differently. The Potter novels end with the hero’s triumph, albeit a bittersweet one (RIP Dobby, Fred Weasley, Professor Lupin, etc). Il Trovatore ends with the unexpected triumph of Azucena, whose true motives only become clear at the very end. Therefore, Verdi’s conception of the mother figure is far less altruistic than Rowling’s. But again, the stark contrast of this difference shines a light on the nature of these works: one is meant for children and teenagers, the other for the world’s grand opera stages. One seeks to affirm the power of love to triumph over hate; the other seeks to demonstrate the way revenge can tear families apart. Both have the power to move audiences, generate massive fan bases, and invite us to make hidden connections to our own lives.

The writer, an intern in Lyric’s marketing and communications department in spring 2018, is currently the relationship marketing associate at the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.