October 24, 2019

Rape, revenge, love: the DON GIOVANNI puzzle

By Martha C. Nussbaum

Don Giovanni is a glorious enigma. Its music is so enthralling, and yet its sentiments are confusing, perhaps also confused. Is the listener to be captivated by the Don, and to feel a sense of loss when he leaves the world – as many romantic interpreters have believed? If so, there is one sort of problem: for this Don is a really horrible person, who, despite a certain boyish energy and charm, has no sympathy at all for anyone else and who uses a combination of class dazzle and sheer force to make his conquests. If audiences of a bygone era (or, at any rate, their male members) viewed this behavior indulgently, surely audiences today cannot.

Donna Elvira (Ana María Martínez) is unnerved when Don Giovanni (Mariusz Kwiecien) reappears in her life: Don Giovanni at Lyric, 2014|15 season.

Mozart typically portrays this sort of domineering masculinity in a very negative light (think of the Count in The Marriage of Figaro); he prefers men who approach women with gentle and tender sentiments (even when, like the lovers in Così fan tutte, their emotions aren’t going to last very long). Or is the Don a scoundrel for whose punishment we should be rooting all the time, as librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte’s subtitle, “The Profligate Punished” (Il dissoluto punito) suggests? If so, there is another sort of problem: Mozart is virtually obsessed with the repudiation of a morality based upon revenge. Again and again, in Idomeneo, The Marriage of Figaro, The Magic Flute, and, most obviously, La clemenza di Tito, mercy and gentleness win out over vindictiveness and hate – not just in the libretti, but also, and more powerfully, in the music.

Where, then, in this opera, is the Mozart whose gentle humanity we love? It’s tempting to agree with the great opera critic Joseph Kerman (1924-2014): Da Ponte gave Mozart a libretto that was in some ways a bad fit for the composer’s own emotional preoccupations, and Mozart did the best he could.

Before we conclude that Kerman is right, however (and I think he is at least partly right), we need to consider the romantic interpretation, since it is so influential. According to a long line of (male) critics, beginning at least with the 19thcentury Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813|1855), and including my own teacher, the distinguished British philosopher Bernard Williams (1929|2003), the Don is an emblem of erotic striving and sexual energy, a kind of life force whose doom leaves the world gray and impoverished. Such interpreters hear in the opening D minor of Don Giovanni’s overture the heralding of a new post-baroque and post-religious era (never mind that this same music is later associated with the very conventional, religious Commendatore). They go on to represent the Don as eros incarnate. But can this be correct, when the Don needs force so often to achieve his ends (even with Zerlina, initially interested though she is)? And when he so conspicuously lacks characteristics that Mozart elsewhere associates with the ability to inspire love in a woman – such as tenderness, humor, playfulness, an inner life?

Susanna (in Figaro) says of Cherubino, “If women love him, they surely have good reason.” Could anyone say this with a straight face about the Don? Rather, we should say, “If women love him, they’re bewitched by wealth, class, and false promises.” He certainly lacks the appealing playfulness of the Don in Tirso de Molina’s The Prankster of Seville (El Burlador de Sevilla, 1630), probably the first literary example of the Don Juan legend. He doesn’t have ideas either, as Molière’s Don Juan, another of Da Ponte’s sources, conspicuously does. Taking these characteristics away, Da Ponte leaves only hollowness in their place. Mozart further emphasizes the Don’s hollowness by refusing him a full-scale aria, in which inner thoughts and feelings could be explored. He’s little more than a series of elegant poses: a “No-Man” (as musicologist Wye Jamison Allanbrook [1943-2010] puts it in her subtle and important study of Don Giovanni and Figaro). And lest we try to reply that rape was not viewed in such a negative light in Mozart’s time, we should remember that even the not-very moral Leporello protests, “But Donna Anna didn’t ask to be raped.”

Many Mozart devotees make a pilgrimage to Prague’s Estates Theater, where Don Giovanni premiered in 1787 and is still performed today.

Nor is the Don’s music (as opposed to the opera’s) at all innovative or romantic. It is either banal, if pleasing (the serenade) or manic (the so-called “Champagne Aria,” lasting a mere 90 seconds), or borrows a spurious tenderness in the service of violence to come (“Là ci darem la mano” – in which, as Kerman noted in a 1990 essay, all the real musical invention is supplied by Zerlina). We have only to compare this “hero” with genuine romantic heroes, such as the Werther of Goethe and Massenet, in order to see that he’s not that sort of thing at all: no boundless inner world, no surging love, no subjectivity at all, musical or verbal.

I fear that these romantic male critics have been duped by the evident power of Mozart’s music into locating this “demonic” power in the person of the Don, where it surely does not reside. Perhaps the idea of boundless sexual energy without love or tenderness has appeal for men of a certain age – but that doesn’t license projecting those sentiments onto Mozart, who associated music of enormous power and gravity with the critique of the Don and his actions.

So far as our first enigma is concerned, then, the opera gives a clear answer: the Don is a horrible and empty person, whose passing we should not lament, and who surely is not (as Bernard Williams oddly wrote) the source of the vitality of all the other characters. Mozart never glorified male abuse and silencing of women, and in some ways he was a man more of our current era than of his own. Da Ponte was different, and perhaps some of his Donnish sensibility creeps at times into the libretto he wrote for Mozart – here Kerman is insightful. Nonetheless, even the libretto clearly condemns the Don’s behavior, so there is little if any tension between libretto and music.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, painted posthumously in 1819 by Austrian artist Barbara Krafft.

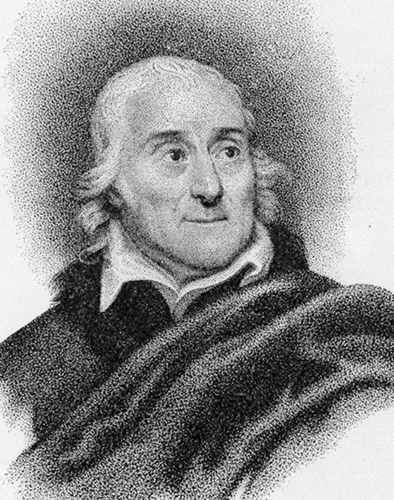

Mozart’s librettist, Lorenzo Da Ponte.

Our second enigma is far more difficult, since the desire for revenge motivates all the other characters of the opera much of the time, and it surely gives the plot its structure. Here Kerman’s idea fully convinces: the libretto requires revenge, but Mozart evidently has a hard time subscribing wholeheartedly to the cruel punishment of anyone – a reason why the final ensemble has always been felt unconvincing and flat, and has sometimes been cut in performance, including by Gustav Mahler (although this practice is seldom encountered today). Does Mozart, then, find any way to extricate himself from the trap set for him by Da Ponte’s libretto? The trap of making revenge look fitting and mercy inappropriate?

Searching for an alternative and more typically Mozartean emotional statement, one might first try turning to Don Ottavio, who surely does express sentiments of sympathy and altruism that are highly Mozartean, and closely linked to Mozart’s rejections of revenge in other operas – least, in his beautiful aria in Act One, “Dalla sua pace.” But this aria was added for the Vienna performance at the request of a singer who had trouble with the florid runs of the Act Two aria, “Il mio tesoro” (which was cut on that occasion), so it can’t have been an original part of Mozart’s conception. And in any case, Don Ottavio, though sensitive and in many ways appealing, is a thoroughly conventional figure, and throughout the opera he pursues revenge as much as anyone else.

Donna Anna (Marina Rebeka), desperate that justice be done after finding the body of her dead father, the Commendatore: Don Giovanni at Lyric, 2014|15 season.

The answer, then, must be found by turning to the opera’s trio of remarkable women, surely the prime sources of its extraordinary vitality and musical glory. Though required by the plot to approve of the punishment of the Don, each of them has a moment in which she turns away from the morality of revenge to embrace a richer conception of love. For Zerlina, access to tenderness is easy, since, as a young peasant woman, she has no outsize attachment to honor (for Mozart always a trap) to stand in her way. In the sensuous and tender “Vedrai carino,” she says that sexual love can heal the wounds created by a vain competition between men: the body affirms what hierarchical culture so often denies. James Joyce knew what he was doing in Ulysses when he imagined the earthy Molly Bloom singing this role (as, indeed, when he, or, rather, his protagonist Leopold Bloom, implicitly cast the Don as Blazes Boylan, Molly’s empty and boring lover).

Masetto (Michael Sumuel) and his fiancée, Zerlina (Andriana Chuchman), making merry with their friends: Don Giovanni at Lyric, 2014|15 season.

The two aristocratic ladies have a more difficult time with tenderness since, in an honor culture, outraged honor seems to demand steely revenge. Donna Anna even puts this honor culture in its best possible light in her splendid aria, “Or sai chi l’onore,” which makes the demand for bloodshed sound almost like a high-minded assertion of human dignity with no downside. By the opera’s end, however, Donna Anna sings a different tune, literally: the stately, flowing first half of her aria, “Non mi dir,” in which she expresses tenderness to Ottavio, and its vigorous second section, with its excited hope for a future of love with him. Both sections sound so unlike her earlier stern self that they puzzle many interpreters. (Peter Sellars even staged the aria with Donna Anna high on drugs, to explain the sudden shifts of mood.) Could one not say, however, that Anna, who knew how to be a lady, has now discovered how to be human?

Donna Elvira (Ana María Martínez) arrives in Seville, searching for Don Giovanni: Lyric production, 2014|15 season.

Donna Elvira is all along, in a sense, the opera’s emotional center, since it is through her distress and distraction that we see what this Don is worth and what his vaunted glory comes to. It is surely not very satisfactory, however, that the way in which she departs from the revenge mentality and embraces compassion (“pietà”) is through a renewed love for the Don! It would have been nicer, one feels, if she could have found a new love interest – but the plot does not provide one for her. Still, her emotional shift is the focus, and its unsatisfactory object is less important. “Mi tradì quell’alma ingrata” is another aria added at the Vienna premiere and so was not an original part of the score or libretto. But in this case the opera’s overall plan appears to require the addition: the plan is really not about the Don at all – it’s about the emotional journey of these three women, each wronged, each tempted by revenge, but each, in the end, overcome by love. And it’s also about how each, through that change, awakens to a life that is less exhausted (for revenge is very fatiguing), less strained, more capable of genuine delight and happiness.

That, I believe, is Mozart’s plan. Or, rather, it’s what, being Mozart, he made of a libretto that was at best an incomplete fit with his insights and sensibilities. Don Giovanni remains a puzzle: but its searingly powerful music and its complex, often surprising emotions give listeners an unparalleled journey into the human heart.

Martha C. Nussbaum, Ernst Freund Distinguished Service Professor of Law and Ethics at The University of Chicago, has also taught at Harvard, Brown, and Oxford universities. Her latest books are The Monarchy of Fear: A Philosopher Looks at Our Political Crisis (2018) and The Cosmopolitan Tradition: A Noble But Flawed Ideal (2019). She is the winner of the 2016 Kyoto Prize in Arts and Philosophy and the 2018 Berggruen Prize for Philosophy and Culture.